The Hitchcock Conversations is an ongoing project between me and James W. Powell, in which we study Alfred Hitchcock’s filmography in chronological order. I’ll be publishing one conversation per week.

The Hitchcock Conversations is an ongoing project between me and James W. Powell, in which we study Alfred Hitchcock’s filmography in chronological order. I’ll be publishing one conversation per week.

(By necessity, spoilers ahead!)

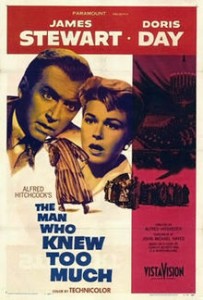

Synopsis: A family vacationing in Morocco accidentally stumble on to an assassination plot and the conspirators are determined to prevent them from interfering.

James: This remake surpassed my expectations. I remember enjoying this version of The Man Who Knew Too Much the first time I saw it, but I have even more respect for it now. It’s better on most levels than the 1934 original, and I found myself totally caught up in it—more so than many of the other Hitchcock films. At times, the raw emotion of these parents searching for their kidnapped son is palpable. As in all of Hitch’s great films, he shows us people thinking. But here, we really feel them thinking.

Jason: I enjoyed this film, too, but I have to say that it took me a while to get into it. You know what was holding me back? James Stewart. At the beginning of the film, he felt very arch to me, unnatural, as if his performance was getting in the way of the story. More than that, I didn’t like his character, Dr. Ben McKenna—this fussy know-it-all who makes an ass of himself more often than not. I mean, I liked Stewart far more in Rear Window. However, at about the halfway point of The Man Who Knew Too Much, when Ben starts to take action, Stewart comes more to life, and it’s then that this movie took off for me. So, a disappointing first act gives way to some good suspense and real emotion.

James: I agree about Stewart. In the early going, I felt like I was watching Jimmy Stewart, not his character Ben, the guy who gets caught up in the adventure of the plot.

Jason: You could make an interesting distinction between the original film and the new one, in that the original is more of an ensemble piece and the new one is more of a star vehicle for Stewart. As such, it’s clear that Hitch let Stewart have a lot of freedom in his characterization, letting the actor inject various “Stewart-isms” into the character. For example, that scene in the restaurant in which we see his bumbling lack of table manners: It’s typical Stewart humor, but it’s illogical. Wouldn’t he have learned local customs while he was there during the war?

Jason: You could make an interesting distinction between the original film and the new one, in that the original is more of an ensemble piece and the new one is more of a star vehicle for Stewart. As such, it’s clear that Hitch let Stewart have a lot of freedom in his characterization, letting the actor inject various “Stewart-isms” into the character. For example, that scene in the restaurant in which we see his bumbling lack of table manners: It’s typical Stewart humor, but it’s illogical. Wouldn’t he have learned local customs while he was there during the war?

James: I’m beginning to wonder if Hitch let his actors have too much freedom with their characters. I think some of his earlier works without star power are a little more pure. But by 1956, he’s got big stars in his films because he’s so popular, and the films seem to be less about his work and more about theirs. That’s a hasty generalization, but I seriously wonder whether Hitch would’ve been better off had he cast lesser-known actors in To Catch a Thief and The Man Who Knew Too Much.

Jason: I agree. When I think back on To Catch a Thief, I think of two celebrities just smirking and having fun. I don’t think about an enticing story or cinematic effort. In this film, I think Hitch has encouraged all that ad-lib Stewart bumbling too much. Stewart is best for Hitchcock when he’s not talking—you know, when he’s just watching and agonizing (for example, in the car when he’s worried about his son and how he’s going to tell his wife and what the hell he’s going to do).

James: I had an even deeper problem with Doris Day, who plays Ben’s wife, Jo McKenna. She was superb in key scenes, such as the one in which Ben tells her their son Hank (Christopher Olsen) has been kidnapped, and pretty much any scene that showcases her motherly nature. But overall, she seemed stilted. I noted several times that she seemed stiff. I’m not exactly sure what it was, but her personality wasn’t vibrant enough for me, especially when considering all of Hitch’s perfectly cast blondes. So, the pairing of Stewart with Day made for some less-than-stellar scenes at the beginning of this film. But as you said, once the action started going, Stewart stepped to the plate and really helped this movie become great.

Jason: Just as a side note, I learned that the scene in which Ben tells Jo about the kidnapping was filmed in one take. Stewart and especially Day nailed it the first try.

James: First take? I believe it. It’s so well done. I doubt Day could’ve done it too many times while maintaining such a high level of emotion.

Jason: But I’m in general agreement about Day. At first, she struck me as completely the wrong type for a Hitchcock flick. And at times, her performance was indeed stiff. But then she burst to life in that scene and ended up delivering one of the most emotionally powerful moments in any Hitchcock film! She’s definitely not a raging beauty in this film, like Grace Kelly was, but she comes across as a cute mom type. Almost as if she was the Meg Ryan of her day.

James: Do you think it was a good or bad thing for Paramount to force Hitch to give Day a song? Part of me likes the fact that music is such a key aspect of this film, and it works very well to have a main character involved in music, too. But part of me felt that it was just a stupid idea forced into the film so that Doris Day, the singer, could have a musical interlude and thus get more tickets sold.

James: Do you think it was a good or bad thing for Paramount to force Hitch to give Day a song? Part of me likes the fact that music is such a key aspect of this film, and it works very well to have a main character involved in music, too. But part of me felt that it was just a stupid idea forced into the film so that Doris Day, the singer, could have a musical interlude and thus get more tickets sold.

Jason: At first, the inclusion of the two Doris Day songs made me bristle. But the more I listened, the more I thought her songs and her singing worked in the context of the film. The character Jo is essentially a retired singer who has decided to give up her career in favor of a quiet life in Indianapolis with her doctor husband. You get the feeling there’s a little friction in their relationship because of this. The first song we hear is the kinda-sad, kinda-regretful “Whatever Will Be” song (“Que sera sera”), and the way she and her son Hank sing it as kind of a lullaby builds their characters and their relationship in a nice way. But what’s especially interesting about the song is that she belts it out at the end to root out Hank from his kidnappers and rescue him. So the song is essential to the plot and her character, because in the end, she’s back on stage, performing. You could say that early in the film, she seems stifled by her husband’s career dominance, but in the end, her “career” is what saves the family and is finally recognized as “legitimate.” I don’t know if I’m making sense.

James: That makes sense. I can totally see that in the film. Here’s this woman who apparently regrets not being able to perform anymore, but now she has to perform or her son dies. I hadn’t considered the fact that it legitimizes her career. So, in that regard, in their possible future, Ben will reconsider and understand that Jo’s singing is indeed important, and will be more open to the notion of Jo returning to the stage?

Jason: That’s the idea. Hmmm, interesting parallel with the original film, then. In the 1934 film, the mother, Jill Lawrence (Edna Best) is an Olympic sharpshooter whose skills come into play at the climax. Similarly, Jo’s musical skills save the day in the remake.

James: I hadn’t thought of that. Good, good. That’s really cool, actually.

Jason: I read that the Doris Day musical element of this film has shades of Marlene Dietrich in Stage Fright. In both cases, the singer stars objected to a song written for them. In this case, Day didn’t initially like the “Whatever Will Be” song, thinking it juvenile. But later it won the Oscar for Best Song and eventually became one of her signature tunes.

James: Very interesting that Day didn’t initially like that classic song.

Jason: I noticed that when Jo is singing “Whatever Will Be” to Hank at the beginning, he’s whistling along with her, just as he whistles later to signal to his parents where he is. Nice foreshadow there.

James: I noticed that foreshadow and actually would’ve liked it had it not been for that damn boy. I mean, his whistling is so high-pitched and awful.

James: I noticed that foreshadow and actually would’ve liked it had it not been for that damn boy. I mean, his whistling is so high-pitched and awful.

Jason: He’s definitely annoying. It’s supposed to be this idyllic bedtime-lullaby scene, but it comes across as fingernails on a chalkboard. That’s unintentionally funny. Speaking of the film’s music, what did you think of the opening card: “A single crash of Cymbals and how it rocked the lives of an American family”? Interesting to think that the family has no idea what significance the cymbals have in the whole scheme of things. It’s the kidnapping itself that “rocks their lives.” And why is “Cymbals” capitalized?

James: Why is that word capitalized? I actually hoped the cymbals would’ve meant something early in the film, too, another foreshadow. Because technically, the cymbals don’t mean anything to the family. Jo doesn’t even know that the assassin, Rein (Reggie Nalder), has been instructed to shoot the prime minister at the moment the cymbals crash. So they really mean nothing to Jo.

Jason: In his book, Donald Spoto thinks there’s a connection between Cymbals and “symbols,” that the crash of cymbals is a symbol for the crashing back together of this family, and he also touches on the importance of music to both this movie and the family. We’ve said that it’s also essential that Jo has returned to the stage at the finale, belting out a tune to save her kid. You get the sense that her love for her musical career and glory is finally accepted within the family dynamic and won’t be pushed aside in the future, as it was threatened at the start. All this music ties together in an interesting symbolic way.

James: What did you think of the villains in this remake? In typical Hitch fashion, we get some bad guys whom we actually get to know as a warm, kindly couple. I’ve always thought the Draytons—Edward (Bernard Miles) and Lucy (Brenda De Banzie)—were a bit creepy, but they’re pleasant enough. So it comes as a bit of a shock to learn that they’re behind the boy’s kidnapping. There are some questions that remained unanswered, though. I don’t think the Draytons really matter in the overall scheme of the plot, but I would’ve liked more information about them. Why do they use a church as their front? How did they hook up with the crooked ambassador in the first place? Stuff like that.

Jason: I think it’s interesting to have characters who are seemingly innocent and kindly at first but end up being evil. But I don’t think Hitch pulls that off very effectively here, and it’s because of the unanswered questions you mention. Sure, it could be said that the Draytons and the whole kidnapping and assassination plot are the MacGuffin, that the story is really about how the McKenna family is brought closer together through their predicament, but in this case, I really wanted some more answers, as you did. At certain points, I wondered how the Draytons have targeted the McKennas, what role Louis Bernard (Daniel Gelin) plays, and why he doesn’t just expose the Draytons in Marrakech. Why is Bernard in disguise when he’s killed? Is it just for the dramatic effect of Ben’s fingers sliding through Bernard’s dark make-up and ending up with dark splotches on them? Why, for that matter, are the Draytons in disguise as tourists? And you raise some very valid points.

James: See, I had many of those questions as well. I remember at one point thinking that a remake of this story, made today, would be a mess if it lingered on too many details and plots within plots, simply because all these details would’ve been answered. At the same time, though, I’m wondering if Hitch should have beefed up the “meaningless MacGuffin” in this case, so that the plot would make more sense.

James: See, I had many of those questions as well. I remember at one point thinking that a remake of this story, made today, would be a mess if it lingered on too many details and plots within plots, simply because all these details would’ve been answered. At the same time, though, I’m wondering if Hitch should have beefed up the “meaningless MacGuffin” in this case, so that the plot would make more sense.

Jason: I’m more and more convinced that Hitch just didn’t mind leaving important plot details unanswered. He just didn’t care about specifics as long as the essential emotions were conveyed. I think we can agree that Hitch cared more about character and emotion and symbolism than details and plot.

James: Oh, I know that Hitchcock didn’t care about specifics, and usually it doesn’t matter. But here, I feel it could’ve helped the film had we known a few more details.

Jason: Yeah, in this case, a little more plot would have benefited even the emotion that’s felt by the characters, and therefore the emotion we feel as an audience. I think it’s essential to understand what’s happening to these characters. Otherwise, we fail to form an adequate bond with them. If there’s too much that we’re questioning about what’s happening to them, we’re distanced from the narrative, asking too many questions when we should be going with the flow, as Hitch wants us to do.

James: Yep.

Jason: Here’s one thing I didn’t get about the beginning of the film, and Louis Bernard’s involvement: He initially mistakes the McKennas for the Draytons (whom we come to find are British Communists), and that’s why he gives them the third degree on the bus. So, in the hotel, he’s essentially spying on them, completely mistaking them for the villains. Did you get that? Am I dense?

James: Yeah, that’s what I saw Bernard doing. But I didn’t catch it until later. So at first, I didn’t understand what it meant when the assassin, Rein, walked in and saw Bernard standing there with the McKennas. For whatever reason, that was the trigger for Bernard to know that he was spying on the wrong couple.

Jason: Okay, so if the assassination plot and the kidnapping are the top-level MacGuffin, what would you say is the film’s central concern, the plot that we should really care about? Is it the well being of the family? Is it the fact that at the beginning, we feel some tension between them, and through the action of the film, they come to value one another and grow into a more cohesive family? If so, is that entirely clear in the film? I’m not sure it is.

James: You’re right, the family aspect of this film isn’t developed enough, either. Not by a long shot. I didn’t even notice that Jo had given up her singing career for Ben until I watched the DVD’s making-of featurette. So I never really felt that tension. In hindsight, I did, but not on the initial viewing. The family coming together at the end, therefore, didn’t seem as important as it could’ve or should’ve been. To me, the McKennas seemed like a fine family. So to see them fixing their problems as they make their way through the plot just didn’t work. Of course, the “let’s find our son” aspects were just fine.

Jason: I’m in a difficult spot with this film. One part of me admires it for its big sequences and for what it’s trying to do, and even in the ways it improves on the original. But another part of me is seeing it as one of the most overrated of Hitchcock’s movies. There’s just not a lot here that’s truly captivating, or at least the aspects that should have a lot of power—and seem like they do have that power, on the surface—break down easily on close inspection. So, did Hitch hope his audience would just lose themselves in what he intended to be a light confection? Or did he really intend this to be a more serious effort, and he just failed to provide adequate depth in the story?

James: I don’t think either is quite right. I think he wanted it to be a bit more than the light stuff we’re used to, but maybe he didn’t understand that the MacGuffin doesn’t fully carry over into a film like this? Or maybe it didn’t matter, and he miscalculated by making it too heavy? Not sure. But it seems that all of the basics are here, particularly the idea of the innocent, ordinary man caught up in something huge. However, The Man Who Knew Too Much seems to have neither the fun of The 39 Steps nor the involving intrigue of a deeper political thriller.

Jason: Yeah, the makings for a truly powerful remake are here, but this family needs more than just the subtle suggestion of conflict. Well, let’s dig deeper. What did you think about Ben and Jo’s marriage? What’s the conflict? What do they have to work through in order to deserve the catharsis they get at the end? I did get a vibe of discontent in their marriage. She seems to resent him for displacing her from the New York high life to banal Indianapolis, as we’ve mentioned. They don’t communicate incredibly well, but they share a light joke here and there. Still, there’s the shadow of conflict. In the end, Jo has to make a horrible decision: interrupt the assassination attempt to save the life of a political figure or remain quiet and save the life of her son. If she makes a sound, chances are that her son will die. She ends up taking the gamble and, as a result, brings a new zest to her family. Hitch makes a huge deal of showing the reunited family in a tiny end scene. Do they deserve that happy-frothy scene? Sure, they’ve struggled, but were they really that bad a family to begin with? Does there have to be such a stark contrast? Is it okay for Hitch to show us the redemption of a family that’s just got some minor communication problems?

James: That’s what I was getting at. In order for the film’s happy ending to actually mean something, we have to see the problems up front. It’s like Spielberg, who always needs to show the happy family reuniting in the end. In War of the Worlds, he hammers and hammers the fact that Cruise and his son don’t like each other, and after everything they go through, their relationship is healed. In The Man Who Knew Too Much, I barely even recognized any initial discord. Sure, I caught the subtle lines here and there, as when Jo complains that there aren’t any big shows in Indianapolis or that Ben could easily perform his practice in New York if he was willing. But that stuff isn’t powerful enough. There isn’t enough dysfunction for me to grant Hitch that ending. However, as I said, the kidnapped-son plot does work and that’s almost enough.

James: That’s what I was getting at. In order for the film’s happy ending to actually mean something, we have to see the problems up front. It’s like Spielberg, who always needs to show the happy family reuniting in the end. In War of the Worlds, he hammers and hammers the fact that Cruise and his son don’t like each other, and after everything they go through, their relationship is healed. In The Man Who Knew Too Much, I barely even recognized any initial discord. Sure, I caught the subtle lines here and there, as when Jo complains that there aren’t any big shows in Indianapolis or that Ben could easily perform his practice in New York if he was willing. But that stuff isn’t powerful enough. There isn’t enough dysfunction for me to grant Hitch that ending. However, as I said, the kidnapped-son plot does work and that’s almost enough.

Jason: Okay, I see where you’re coming from. But I also hate Spielberg’s tendency to, as you say, hammer home his meanings and emotions. I guess you could say Hitch goes entirely the opposite route, trusting more in the viewer to ferret out subtle information about the state of existing relationships. Are we just conditioned to prefer obvious plot points? Given the choice between Spielberg’s hammer and Hitchcock’s more precise touch, I’ll take the Hitch way every time, even though I believe he hasn’t given us enough in this film. That being said, subtlety is what makes a movie like this so re-watchable. I betcha anything more clues about this family would come to the surface on repeated viewings.

James: I’m with you. I appreciate the more subtle hints. But at the same time, there’s such a thing as being too vague. I would’ve liked one concrete piece of evidence that the McKenna family isn’t working together as well as it could. Or one simple scene that shows us their early troubles so that the ending accomplishes more than just giving them their son back.

Jason: You’ve mentioned the drama of the kidnapped kid a few times. I have to admit that the parents’ emotion after the kidnapping is compelling. You can really feel Jo’s frustration and hysteria when she’s been sedated by Ben just prior to learning that Hank is gone. And Jo’s emotional struggle at the climactic moment in Albert Hall is palpable.

James: The parents’ emotion saves this movie. Doris Day really did a fabulous job in key scenes, as we’ve said. Can you imagine having to make such a decision: the well being of your son versus foiling an assassination attempt? And Stewart managed some nice scenes, as well. I like how Ben walks out on Jo’s welcome party just after he gets off the phone with “Ambrose Chappell,” the taxidermist whom he thinks (mistakenly) is connected to the kidnapping. That was nicely played. And the tension of that Albert Hall climax is fantastic. We really feel what it must be like to be the parents of a kidnapped little brat. Man, I wanted to reach into the screen and beat Hank more than once.

Jason: I completely agree about Hank. Isn’t that funny, though? In both versions of The Man Who Knew Too Much, we thought the kidnapped kid was annoying. In the first film, it was Nova Pilbeam who played the little girl getting in the way of the Olympic ski event and generally being a nuisance. In this film, little annoying Hank delightfully rips the veil off an Arab woman and whistles like a banshee.

James: Also, I thought it was interesting that this film starts in third-world Marrakech and ends in the most upscale of places: Albert Hall in the center of bustling London. We go from poverty to posh.

Jason: Okay, let’s talk about the ending. It’s almost as if the entire movie is building up to this, surely the most ambitious climax in a Hitch film so far, and even better, it’s actually a double climax—the big sequence at Albert Hall and the rescue of the boy at the ambassador’s mansion—and I noticed right away that the climaxes sort of echo each other. First, let’s talk about the concert sequence. It’s a 12-minute wordless sequence, practically a silent-film scene put to the key musical selection, Storm Cloud Cantata. This scene strikes me as brilliantly edited, moving back and forth rhythmically between Ben, Jo, the concert itself, the ambassador, and Rein, the assassin, who is just deliciously evil. This guy just creeped me out, man. Those teeth!

James: Rein is perfect in every way. What a creepy dude.

Jason: “You have a very nice little boy, madam. His safety will depend on you tonight.”

James: This ending totally works for me. Hitch’s decision to go “silent” is brilliant. It adds to the tension, because you don’t know exactly what the characters are saying but it’s quite clear because of their situation and the body language. (Although, as an avid film buff, I’d love to see the footage with the actual dialog, just to compare and get a better understanding of how it works.)

Jason: Yeah, the decision to go “silent” is genius. It puts all the audio focus on the piece of music that’s driving the suspense. We’re just waiting for that climactic crash of cymbals, waiting for the inevitable buildup toward the assassination attempt. I felt that I could essentially understand what Ben was shouting to the policeman guarding the ambassador, so dialog would have been superfluous and taken away from the extreme focus on the music.

James: Let me step back a bit. The ending’s drawn-out tension is fabulous, yes. I mean, it’s really powerful. I was on the edge of my seat. I kept thinking “just do something already” to break the tension. It’s a nice, taut scene. But I really had to suspend my disbelief. It felt wrong that Ben could run around from box to box, or that Jo would be able to stand where she was in the aisle, or that there weren’t more policemen and government agents all over the place.

Jason: Yeah, I felt that, too. I was able to suspend that disbelief pretty readily, though.

James: But Jo’s indecision is amazingly well done. I mean, I totally felt what she was going through. As you said, the editing is perfect. It amplifies this feeling of solitude amidst an audience full of people.

Jason: Which echoes Hitch’s love for portraying danger in seemingly harmless settings. So Doris Day has at least two superbly acted moments in this film, and yet when I think of her, it’s not with a lot of admiration. I agreed earlier that she seems stiff now and then in The Man Who Knew Too Much, but there’s no denying that she delivers the goods in key scenes.

James: I absolutely love the fact that Bernard Herrmann plays the composer at Albert Hall.

Jason: I know! Just seeing Herrmann’s name on the marquee is a kick.

James: I would have liked more tension in the second climax of the story. The one at Albert Hall is intense, but the second one, at the ambassador’s mansion, isn’t so much. I think it’s because the bad guys aren’t front and center. I see how the two climaxes echo each other, and I appreciate that, but I wanted the kid to be in a bit more peril, or I wanted there to be more of a chance for something to go wrong.

Jason: Yeah, the kid should be in more peril, but at the same time, I really admired the way Hitch characterized Lucy Drayton in this scene. In a way, she’s going through a similar kind of indecision that Jo went through at Albert Hall, agonizing over the well being of the kid versus the success of the kidnapping. And I found it interesting that both “climaxes” end in falls, the first one when Rein falls from the balcony and the second one when Edward Drayton falls down the stairwell, Hitch’s eternal symbol.

James: I love that Lucy’s indecision parallels that of Jo, but something still bothers me about that second ending. It’s not bad, mind you. I just think it could’ve been amped up. Maybe it’s just the way Mr. Drayton chooses to kill the boy . . . by “taking him downstairs.” There’s nothing sinister about that. Or rather, there isn’t enough tension in that. Now, if Ben had arrived to save the day just as the boy is being shoved down the stairs . . . (or better yet, after the little booger got killed) . . . well, that might have been better. I wonder if it would’ve been a more intriguing moment had Drayton gotten to the bedroom before Ben did. How might that have played out? Sure, it would’ve taken the action off of Ben and focused more on the villain, but it might’ve been more interesting . . .

Jason: Not sure about your hypothetical situation, but I do like the reunion scene between father and son. In general, though, you’re right, the tension could have been amped. I wonder how much of that is our 21st century expectations talking, though? We’re pretty desensitized from this distance. Was it enough in 1956 to merely suggest some kind of harm might come to Hank? At that point in our history, the Soviet Union and the threat of Communism were themselves twin specters of doom, so maybe just having Hank in their hands was enough to induce terror in the audience?

James: You know, I hadn’t thought of that. I’m usually good about putting myself in the time period, but this time it didn’t even cross my mind. But yeah, I bet back then just having the kid in the hands of the Communists was heavy enough. (Just as seeing Grace Kelly in that bathing suit in To Catch a Thief was probably risqué for the time. too. Any time you want to talk about Kelly again, you just let me know.)

Jason: Which brings to mind an interesting contrast between the old and new versions of this film: The first one played against the backdrop of Hitler and Nazism, and this one plays against the Soviets and Communism.

James: I wonder if today we’d have the boy kidnapped by terrorists. What are your thoughts about the police in this film? The two policemen that come to mind are the French police inspector (Yves Brainville) and the Scotland Yard detective, Buchanan (Ralph Truman). I thought that both characters could’ve had bigger, more important roles. I understand Hitch’s dislike of police, but it seems that these two are almost non-characters. They feel flat. A little color or characterization could’ve helped in a big way.

James: I wonder if today we’d have the boy kidnapped by terrorists. What are your thoughts about the police in this film? The two policemen that come to mind are the French police inspector (Yves Brainville) and the Scotland Yard detective, Buchanan (Ralph Truman). I thought that both characters could’ve had bigger, more important roles. I understand Hitch’s dislike of police, but it seems that these two are almost non-characters. They feel flat. A little color or characterization could’ve helped in a big way.

Jason: I felt the same as you: The policemen are non-entities. They felt as if they were there only because it would have been unbelievable had they not been a presence at all. Hitch was obviously more interested in Ben and Jo doing the police work, so the real police would just get in the way.

James: What did you think about the humor in this film? There are two key scenes that are lighthearted to some degree. The first is the restaurant scene, when Ben falls all over himself. This is one of the scenes when I thought I was watching James Stewart, not the character. But more than that, it really burned me how easily Ben changes his tune about Bernard. At first, he sticks up for the man. Then, after one word from his wife, he’s suddenly about to rush over and yell at the man. What’s up with that?

Jason: Yes, that restaurant scene completely turned me off. The humor felt forced, as if the scene was improvised on the spot. And the intrigue of it, with Bernard watching from the next room, was undeveloped. You’re totally right about Stewart’s reaction to Bernard. At first, Ben casually disregards Bernard’s behavior, and then immediately after his wife’s comment, he’s itching to confront the man. Makes no sense. You know, Stewart is always heralded for his ability to become the Everyman character, but I couldn’t have felt further away from the personality and character of Ben McKenna—at least at the beginning. As I said, he felt arch and unconvincing.

James: The second humorous scene occurs in the taxidermist’s shop owned by “Ambrose Chappell,” when everybody ends up in a brawl that’s the result of Ben’s misunderstanding. I actually like that scene quite a bit. It’s an important “wild goose chase,” but it’s also quite humorous.

Jason: The taxidermy scene is very interesting. I like how it turns out to be a total red herring, even though it feels menacing. And I like how the taxidermy foreshadows Psycho. I just like the whole nervousness of the approach to the shop, and seeing Ben talking cautiously with the two “Ambrose Chappells,” father and son. All this, of course, before we find that Ambrose Chapel isn’t a person, but a place. One of the nicer moments in this film, I think.

James: I hadn’t considered the taxidermy as a precursor to Psycho. I like it, though. A lot. Nice! And I really like the fact that Ambrose Chapel is both a man and a place. What a great way to get the plot moving and have Ben travel down the wrong path. I enjoyed the moment when Jo and her party friends figure it all out. Nicely done.

Jason: Oh, there’s another humorous scene in the midst of the intrigue, and that’s when Ben and Jo are at Ambrose Chapel, and they’re murmuring things to each other as they sing with the assembly (“Look who’s coming up the aisle!”). That was a nice moment taken straight out of the original, between Bob Lawrence (Leslie Banks) and Clive (Hugh Wakefield).

James: Yeah, that’s actually a pretty funny scene. (I wonder why he took out the original’s brainwashing scene!) I like the church scene, but I still wonder why it’s there. Why is the church the Draytons’ cover? Doesn’t make much sense.

Jason: Yep, the whole church scene here is nearly as nonsensical as it was the first time. We haven’t talked a lot about similarities/differences between the two films. Anything else strike you? One thing I think this film is missing is the power of Peter Lorre’s performance as Abbott. A truly magnetic villain.

James: Oh, yeah. I totally wanted to point out that the Lorre character is missed. I thought he was the highlight of the first film. I think the Draytons work fine in the remake, but Lorre definitely had something going for him.

Jason: I’ll tell you, though, I think the most interesting character in this movie is Lucy Drayton. I think she really comes to care for Hank while he’s in her charge. I mean, she actually sacrifices her husband for him. Perhaps she yearns for a child of her own?

James: I like how Lucy Drayton tells that creepy woman that she needs to be nicer to the boy. That’s a telling scene that plays nicely with her change of heart later in the film.

Jason: One interesting tidbit gleaned from the Spoto book: The story of this The Man Who Knew Too Much remake is characterized by a series of interruptions. The McKennas and Bernard are interrupted by Rein at their hotel-room door. They’re also interrupted by the Draytons at the restaurant. Ben and Jo are interrupted by Jo’s showbiz cronies at the hotel in London. And Jo’s two big emotional scenes are interrupted—the first one by a sedative, and the second one by her own scream. Spoto even goes so far as to define this scream as the scream of childbirth: It brings her son back to her. In essence, it’s the “second child” that she asks Ben about early in the film. On these latter points, I think Spoto is reaching, but I like the enumeration of interruptions, or accidents, which Spoto thinks are very important to Hitch’s work: “Hitchcock’s narrative world is interlaced with accident, which can be identified as the single crucial element in virtually every one of his films.”

James: I like the idea of giving birth to their second son. Or at the very least, of no longer needing another baby because she’s getting her first back. I like that quite a bit. And yes, we’ve seen countless accidents and chance encounters in Hitchcock’s films. An accident or chance meeting almost always sets off the key action. But even deeper into a given film, the story takes important twists and turns as a direct result of these accidents. Hitch is a master of making such chance moments plausible and entertaining. Sometimes, though, the accidents are poorly conceived and come off as unrealistic.

Jason: True.

James: Did you catch Hitch’s cameo? I know where he was, but I must’ve blinked this time around.

Jason: I caught Hitch, but only because I knew where to look for him. He was facing the crowd of performers in one of the Marrakech scenes, so you only see him from behind.

James: Did any of this film remind you of Raiders of the Lost Ark? Certain moments and camera angles in the Marrakech sequences totally reminded me of the Cairo scenes in Raiders.

Jason: I did get a whiff of Raiders of the Lost Ark, but I think it was only because the setting was similar, and the Arab chase through the narrow streets was similar.

James: Could be just the similarities in the locations, but I like to think Spielberg paid some sort of homage.

Jason: How about this film’s atrocious dubbing? Why do you think it was so bad? I mean, it was horrendous, as if the dialog was recorded later without actually looking at the action onscreen.

James: The dubbing was ridiculous. I know the sound crew didn’t have the sync machines common today, but come on! It was so bad. You’d think they could have at least eyeballed it a bit better.

Jason: You mentioned Grace Kelly earlier. I read in my bio that Hitch wanted to reunite Stewart and Kelly for this film as an “old married couple,” almost like a sequel to Rear Window. Apparently, a contract dispute got in the way of this. Otherwise, it almost happened. But after this point, 1956, Kelly retired from film and would never be available again. Too bad. I think a Stewart/Kelly reunion would have been spectacular.

James: That would’ve been fabulous.

Jason: A nice note to end on: 1956 is the year Hitch began the Alfred Hitchcock Presents TV show, which really catapulted him to fame. I mean, he was a pretty famous director before this, but the TV show would make him a household name.

James: Man, I can’t wait to dive into that show.

Jason: Same here.

James: You know, it’s weird that we both started out saying we really liked this film, but there are several aspects of the film that we both hated or disliked.

Jason: I wouldn’t say that I loved this film. In fact, on first viewing, it left me pretty cold. It was only on reflection of what the characters went through that I began to admire it. But yes, there are many aspects to this film that don’t quite work for me.

I enjoyed reading the comments on “The Man Who Knew too Much”, my favorite Hitchcock film. I watch this film over and over again. As an avid Thriller/Suspense fan, I found it odd that this movie is never mentioned as one of Hitchcock’s greatest, or at best, one of the top thrillers of all times, as the other Hitchcok films are portrayed. When I seached the web, I got the impression it was possibly because the first film was being evaluated rather than the remake. I have never seen the original film, but the 1956 version was intriguing. The McKenna’s seemed to be an average American Family for that time period. I was the same age as the character Hank, played by Christopher Olsen. A sequal would have been interesting, because then we would have known if Jo had the other baby she discussed with her husband early in the 1956 film.

Thanks for reading and for your comments! I highly recommend watching the original, if only to compare/contrast the approaches to the story.