After watching nearly all of Alfred’s Hitchcock’s films (save for a few obscure early offerings), I decided to rank them—42 of them!—in order of preference. See if your opinions jibe with mine! Here we go, starting from the top …

After watching nearly all of Alfred’s Hitchcock’s films (save for a few obscure early offerings), I decided to rank them—42 of them!—in order of preference. See if your opinions jibe with mine! Here we go, starting from the top …

- Psycho (1960)—Hitch’s tiny little horror flick, shot on a shoestring, turns out to be a legitimate masterpiece, a groundbreaker of the genre as well as his most shocking film ever. This film showcases Hitch’s flair for audience manipulation, killing off the star halfway through and leaving us in helpless shock for the rest of the movie. (A+)

- Vertigo (1958)—This film has a smothering, obsessive depth, and it’s probably the Hitch film I most want to view again, immediately. This is, through and through, a story of obsession, and the way it spirals in on itself is reflected in the way its audience reacts to it. It has a strong grasp of psychological tragedy and devastation. (A+)

- Shadow of a Doubt (1943)—This tale of two Charlies is a perfectly structured psychological thriller and Hitch’s first real examination of America and its morals and values. This is the kind of film that provides endless rewards on rewatching, revealing layer after layer of symbolic underpinnings and pitch-perfect character facets. (A+)

- Notorious (1946)—Spectacular, mesmerizing Hitchcock. Not one scene is wasted. The escalating sense of tragedy between its two main characters is compelling, elevating a political romantic thriller to Shakespearean heights. Cary Grant and Ingrid Bergman provide peerless chemistry. This is a dark fairytale masterpiece. And it’s got a definitive use of Hitch’s MacGuffin. (A+)

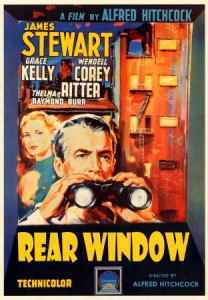

Rear Window (1954)—Hitch’s ode to marriage and love is an intricate web of voyeurism and symbolism. James Stewart and Grace Kelly (mmmm, Grace Kelly) resonate as a playfully troubled couple whose potential futures are mirrored in the various New York apartment windows that Stewart’s telephoto lens peers into. The film is also a cracking good thriller. (A)

Rear Window (1954)—Hitch’s ode to marriage and love is an intricate web of voyeurism and symbolism. James Stewart and Grace Kelly (mmmm, Grace Kelly) resonate as a playfully troubled couple whose potential futures are mirrored in the various New York apartment windows that Stewart’s telephoto lens peers into. The film is also a cracking good thriller. (A)- Strangers on a Train (1951)—This tale of a psychopath’s notion of criss-crossing murders is as psychologically compelling as it is thrilling. The main characters achieve a strangely symbiotic link, and this yin-yang notion flows throughout the rest of the film, which is brimming with potent symbolism. (A)

- The 39 Steps (1935)—This is a very rewarding early film, much more mature than anything preceding it. Hitch is completely into his groove with this “wrong man” story, twisting and turning the story for maximum entertainment. It’s got the primitive nature of an early film, but it boasts great characters and performances married to a terrific story. (A)

- Foreign Correspondent (1940)—Amazing set pieces and action sequences catapult this “lesser” Hitch flick (which could be considered an unofficial remake of The 39 Steps) triumphantly to the level of the classics. This is a real ripsnorter, with dynamic leads and creepy villains. This is Hitch’s first great, truly American film, complete with fun war propaganda. (A)

- Rebecca (1940)—Hitch’s first film made in American under stifling producer David O. Selznick, Rebecca seems compromised of any real Hitch influence, but it’s a terrific story nonetheless. Full of lush style and potent symbolism, the film really intrigues with its gothic mix of doomed romance and madness. Joan Fontaine is a wonder to behold. (A-)

- I Confess (1953)—Perhaps Hitch’s most personal film, I Confess is mature and haunting, full of shadows and the machinations of faith. Method actor Montgomery Clift powerfully elevates the level of Hitch’s usual performances, adding to the realization that I Confess is one of the director’s most important but forgotten films. (A-)

- The Wrong Man (1956)—Based on a true story, The Wrong Man nevertheless is quintessential Hitch storytelling, digging deeply into his all-time favorite theme (the innocent man wrongly accused). Henry Fonda and Vera Miles deliver searing performances that we rarely hear about. The only drawback? A hugely disappointing final moment. (A-)

- The Trouble with Harry (1955)—The first pure taste of Hitch’s black sense of humor, The Trouble with Harry benefits from the director’s TV experience with Alfred Hitchcock Presents. This tale of a corpse that just won’t go away is a trifle, but it’s also a marvelously underplayed look at the dark crevices of small-town America. (A-)

North by Northwest (1959)—Hitch’s final, big-budget take on his enduring “man on the run” plot is a lot of crazy fun, but it’s a bit hollow at the center. Cary Grant is perfectly cast against a sly James Mason (perfectly embodying the high-class, silk-voiced villain). With this one, you just have to sit back, bring on the popcorn, and have a blast. (B+)

North by Northwest (1959)—Hitch’s final, big-budget take on his enduring “man on the run” plot is a lot of crazy fun, but it’s a bit hollow at the center. Cary Grant is perfectly cast against a sly James Mason (perfectly embodying the high-class, silk-voiced villain). With this one, you just have to sit back, bring on the popcorn, and have a blast. (B+)- The Lady Vanishes (1938)—Interesting variation on the “closed room” mystery, in which the mystery takes place entirely aboard a train. This film introduces many key Hitch themes that he’ll explore throughout his career. Terrific sly humor and a couple of charismatic leads—not to mention a quintessential MacGuffin—make The Lady Vanishes one of the greatest early Hitch efforts. (B+)

- Stage Fright (1950)—A surprising delight, Stage Fright marks a big return to form for Hitch, who had been foundering after his departure from the clutches of David O. Selznick. This interesting, deceptive take on the “wrong man” theme is a riotous joy, combining fun characters with clever situations. Its lack of noteworthy stars and careful characterization is a minus. (B+)

- Suspicion (1941)—RKO’s refusal to let Cary Grant portray a villain leads to an interesting story: Rather than a story of the dawning realization of one man’s villainy, Suspicion is about one woman’s psychological breakdown in the face of mounting circumstantial evidence. Hitch provides a good mix of humor and paranoia, and the leads are magnificent. (B+)

- Frenzy (1972)—Here’s a surprisingly assured film from Hitch’s later years, an amalgam of favorite themes and images woven with the blackest of humor. A lack of real character development (and a preponderance of ’70s clothing and hairstyles) keeps this one from being a classic, but there’s lots to admire, including Hitch’s first (and only) uses of nudity. (B+)

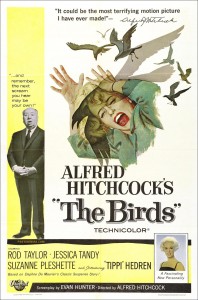

The Birds (1963)—A sprawling, episodic treatment of another favorite Hitch symbol, The Birds is not so much a narrative as a study of chaos. Once you get a handle on how the seemingly random bird attacks coincide with the interaction among a young woman, the man she loves, and his mother, the film opens up in unexpected ways. (B+)

The Birds (1963)—A sprawling, episodic treatment of another favorite Hitch symbol, The Birds is not so much a narrative as a study of chaos. Once you get a handle on how the seemingly random bird attacks coincide with the interaction among a young woman, the man she loves, and his mother, the film opens up in unexpected ways. (B+)- Young and Innocent (1937)—Here’s a fun little movie in the vein of The 39 Steps that’s filled to brimming with all of Hitch’s favorite themes: infidelity, “the wrong man,” the escape across the countryside. This is a surprisingly bright and cheerful film, with young leads and a true sense of innocence. (B+)

- Saboteur (1942)—Saboteur is a big, somewhat slow, sprawling piece of war propaganda, but it’s also a hell of an adventure yarn. Hitch himself laments that it “lacks discipline.” Second-tier leads mean that the film doesn’t boast the charisma of other efforts, and this plot—an innocent man fleeing from the law while trying to clear his name—is already starting to seem overdone. (B)

- Dial M for Murder (1954)—Hitch returns to a single setting (as in Rope and Lifeboat) in this adaptation of a stage play, and the results are mixed. It’s surprisingly talky for Hitch, and it never really rivets its audience as it should. However, some terrific moments, as well as the debut of Grace Kelly, add up to an entertaining crime flick. (B)

- To Catch a Thief (1955)—I was a bit put off by the smirky celebrity of this effort, which sacrifices good characterization and plot for upper-class frivolity on the French Riviera. Cary Grant and Grace Kelly give off a nice, suntanned sheen, and the humor is engaging, but this film is ultimately just cotton candy. (B)

- Family Plot (1976)—Hitch’s final film is a surprisingly youthful, buoyant comedy that touches on many of his favorite themes. The humor proves funnier on further viewings, and although you might wish that Hitch had gone out on a more classic note, this fresh laughfest—complete with a wink from a blonde in the final shot—ends up being a fine, if lightweight, send-off. (B)

- Rope (1948)—Built around its single-take gimmick, Rope takes you in with its sleight-of-hand but ends up telling a disappointingly mediocre story. The lack of a real point of view means that this film, Hitch’s first shot in color, is more of an experimental, single-setting lark than a serious crime film. (B)

- Marnie (1964)—This tale of a blond kleptomaniac and the disturbed gentleman who loves her, only to find out that she’s pathologically frigid, is just short of being great. Some important characterizations at its center, however, are under-developed. However, Tippi Hedren turns in a surprisingly fine performance, despite personal anguish under the controlling hand of her director. (B)

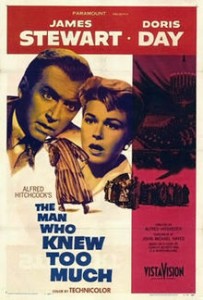

The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956)—Hitch’s only official remake of one of his own films is intriguing in certain ways, mostly due to its larger budget, but some elements of the plot and characterizations are lacking. James Stewart, maddeningly, seems to be playing himself. (B)

The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956)—Hitch’s only official remake of one of his own films is intriguing in certain ways, mostly due to its larger budget, but some elements of the plot and characterizations are lacking. James Stewart, maddeningly, seems to be playing himself. (B)- Spellbound (1945)—Psychologically naïve and overly serious, Spellbound nevertheless compels with its casting, particularly in the case of Ingrid Bergman, who gives her character a convincing sexual awakening in the midst of a crime that could threaten her. The dream sequences are groundbreaking but strangely out of place. (B)

- Lifeboat (1944)—More an allegory about World War II than a true narrative, Lifeboat requires understanding of the world events surrounding it to really appreciate it. Nevertheless, this confined-setting film offers some great pleasures, as well as Hitch’s most clever cameo. (B)

- Sabotage (1936)—Surprisingly effective symbolically, this film doesn’t quite nail its top story, but it offers endless rewards underneath. Hitch continues to experiment technically, getting some things wrong but others very right. And he kills off a kid. (B)

- Torn Curtain (1966)—The troubled production of Torn Curtain resulted in a film that just isn’t entirely sure of itself. Two expensive stars—Paul Newman and Julie Andrews—hobbled Hitch, removing his focus from story elements that needed more attention. The entire third act is a study in disappointment. (B-)

- Blackmail (1929)—A jump in maturity for Hitchcock, Blackmail is his first talkie, although its sound effects often seem gimmicky. Surprisingly well-drawn characters and continuing technical innovation make this one special, despite its age. And it has one of the funniest Hitch cameos. (B-)

- The Paradine Case (1947)—Too long and slow, this film could have been far better had it been more precisely edited. The central relationship, between a defense lawyer and his beautiful client, never catches fire, despite what Hitch wants us to feel. Too many boring court scenes bring the otherwise interesting Paradine Case to its knees. (B-)

The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934)—Boasting the first true use of the MacGuffin, this film is deceptively simple, offering a modest kidnapping story beneath all its intrigue. Hitch continues to develop his obsessions, and we get an appropriately grand finale. Peter Lorre is exceptional. But this film is showing its age. (B-)

The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934)—Boasting the first true use of the MacGuffin, this film is deceptively simple, offering a modest kidnapping story beneath all its intrigue. Hitch continues to develop his obsessions, and we get an appropriately grand finale. Peter Lorre is exceptional. But this film is showing its age. (B-)- The Lodger (1927)—Shades of Nosferatu. Very good silent Hitchcock with excellent technical innovation for the time. The twist at the end really works! But the acting and filmmaking are primitive. (B-)

- The Ring (1927)—In this silent film, Hitchcock delivers his first screenplay, and it’s a romantic comedy! Endless symbolism and sly humor carry the day, but in the end, it’s pretty rough and experimental. (B-)

- Mr. and Mrs. Smith (1941)—This movie feels like a work-for-hire. The smirky Carole Lombard, doomed to die the next year in a plane crash, makes this one bearable, but the film has very little Hitch flavor. It’s a screwball comedy, and it feels banal. (B-)

- Topaz (1969)—Overtly political and overlong, Topaz bears no real Hitch signature and feels like another work-for-hire. Coming late in his career, this film breeds the fear that Hitch is in decline. But it will turn out that the old chap has some surprises up his sleeve. (C+)

- Rich and Strange (1931)—Living up to at least the second adjective in its title, this film is a surreal stab at black comedy and has a trippy final act that kept me thinking. However, the characters aren’t very well drawn, and some of the humor feels forced. (C+)

- Secret Agent (1936)—One of Hitch’s more overtly political thrillers, this film isn’t very involving. The film should’ve focused more on its characters rather than a weak spy plot that doesn’t seem especially well written and ends too abruptly and easily. (C+)

- Under Capricorn (1949)—Here’s a huge misstep in the middle of Hitch’s career, occurring when he had perhaps become a bit too happy with his American success. This reteaming with Ingrid Bergman and Joseph Cotten is turgid throughout, overly talky, and pretentious. A few good moments can’t rescue it from obscurity. (C)

- Jamaica Inn (1939)—For his final British film, Hitch adapted a Daphne du Maurier pirate story pretty lazily. Hitch’s only real motivation for making it was to work with Charles Laughton, so it feels more like a Laughton vehicle than a Hitchcock film. Forgettable. (C)

- Murder! (1930)—This “stagy” whodunit is a fragmented mess, not seeming to know where to begin until halfway through. Its psychology is disturbingly primitive, and the resolution is lazy. (C-)