To a jarring Vangelis crash, Blade Runner opens upon a spectacularly grimy and fiery cityscape teeming with majestic Spinner cars, dully gleaming towers, and poisonous clouds. The Tyrell Corporation can be glimpsed in the dreary distance. An Orwellian eye watches over all, a pillar of fire curling at the edge of its iris.

To a jarring Vangelis crash, Blade Runner opens upon a spectacularly grimy and fiery cityscape teeming with majestic Spinner cars, dully gleaming towers, and poisonous clouds. The Tyrell Corporation can be glimpsed in the dreary distance. An Orwellian eye watches over all, a pillar of fire curling at the edge of its iris.

Who belongs to that eye? The easiest—and literally the most valid—answer is Holden, the doomed blade runner who administers the android-detecting Voigt-Kampff test to Leon at the beginning of the film. But for the sake of this review, it’s much more interesting to step back and let that shifting eye occupy a different socket—that of the critic or essayist. In the case of Ridley Scott’s wildly influential masterpiece, there have been many.

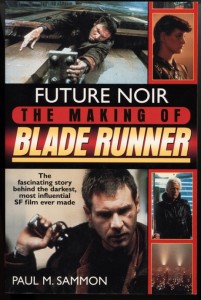

But the latest Blade Runner commentator, Paul Sammon, was actually one of the first. In 1980, Cinefantastique assigned Sammon to cover the film’s production for a double-issue behind-the-scenes cover story. He conducted endless interviews with cast and crew, was present during pre-production, principal photography, and post-production, and finally gathered so much data that it began, he says, “to overflow the boundaries of the original assignment.” The result, in his book Future Noir, is an extremely comprehensive look at Blade Runner. Sammon has the unique perspective of someone behind the camera, but also of someone watching the finished product on the big screen. He’s a “crew member” and a fan at the same time. He can, it could be said, view the film through two very different kinds of eyes.

That parallelism sets the tone for what is an authoritative—though critically one-sided—study of one of the more provocative films in cinema. Though the sum of this movie is greater than its parts, Ridley Scott’s magnum opus is flawed—as other eyes have noted. Some of those critics have valid thoughts worth imparting. In Future Noir, however, you’ll find only brief mention of, say, Pauline Kael’s scathing criticism of the film, followed by in-depth rebuttal and dismissal of that criticism on the part of the filmmakers and Sammon. This is, in short, clearly a labor of love from a devoted fan of Blade Runner. And that’s fine.

If you are, like Sammon (and like me), a devoted fan of Blade Runner, then this book is the ultimate tour guide through the streets of Los Angeles, 2019. You’ll keep Future Noir rubber-banded to your home-video version of the film so that you can flip through the book as you watch the film over and over again, each time catching a tiny detail you missed before.

In fact, the longest and most fascinating section of the book examines, “scene by scene,” the manner in which Blade Runner was constructed during principal photography.” Utilizing those interviews from 1980-1982, along with recent conversations to provide valuable perspective, Sammon creates a virtual team of experts who dissect the film, illuminating background minutiae as well as clarifying the origins of foreground elements. Did you know, for instance, that the snake scale examined by fez-hatted Abdul Ben-Hassan on Animoid Row is actually the bud of a female marijuana plant? Or that Eldon Tyrell himself was originally imagined as a replicant “clone” whose real body was kept frozen in a cryogenic chamber? Or that Roy Batty’s classic “tears in rain” speech was penned by Rutger Hauer himself, moments before filming that wrenching scene? The chapter is choked with such insights, and you’ll find yourself astonished by the attention to detail.

This absorbing enumeration of production trivia is balanced by an equally engaging appendix, in which Blade Runner‘s numerous technical “blunders” are identified and accounted for. Though most of these errors are of the “lip-flap” variety (that is, the dialog on the soundtrack sometimes doesn’t match the movement of the actors’ lips), some are cringingly apparent. Joanna Cassidy’s double in Zhora’s death sequence, for example, looks nothing like the actress. Roy Batty releases his dove, at the end of the film, into an impossibly clear blue sky. Captain Bryant informs Deckard of the escape of five replicants, yet the blade runner retires only four over the course of the film.

This absorbing enumeration of production trivia is balanced by an equally engaging appendix, in which Blade Runner‘s numerous technical “blunders” are identified and accounted for. Though most of these errors are of the “lip-flap” variety (that is, the dialog on the soundtrack sometimes doesn’t match the movement of the actors’ lips), some are cringingly apparent. Joanna Cassidy’s double in Zhora’s death sequence, for example, looks nothing like the actress. Roy Batty releases his dove, at the end of the film, into an impossibly clear blue sky. Captain Bryant informs Deckard of the escape of five replicants, yet the blade runner retires only four over the course of the film.

Captain Bryant’s blunder is a fitting segueway into one of the film’s more controversial suggestions—that Deckard is himself a replicant. The debate has been a vocal one, and still is. Supporters of an android Deckard point to the seemingly desperate clutch of photographs surrounding his piano, to his knowledge of Rachael’s spider memory, and to Gaff’s tinfoil origami unicorn, which echoes Deckard’s dream (in the director’s cut). Naysayers maintain that the film’s emotional impact is deadened by the very idea—what is the point of Deckard’s spiritual growth, his final humanity, if he’s not human? Whether Harrison Ford’s character is a replicant depends on which version of the film you watch, answers Paul Sammon.

And there are several versions. You’re probably aware of the international cut, which replaced scenes of violence excised in the domestic cut, and you no doubt own the director’s cut, which added the unicorn dream and stripped away Ford’s intrusive narration and the appalling happy ending. You might not be aware of what Sammon calls the Workprint, which ran for four weeks at Los Angeles’ own Nuart Theater in 1991 under the misleading “director’s cut” banner. It was nothing of the kind. In truth, it was something even more valuable. Rough-edged, and unfinished in parts, it was actually the version shown to Denver and Dallas sneak audiences back in 1982. The print is full of rare footage, every moment of which is catalogued meticulously in another of this book’s many appendices—including the jaw-dropping moment that finds Roy Batty confronting his maker with the altered line, “I want more life … father.”

Future Noir is a Blade Runner encyclopedia, a painstakingly matter-of-fact reference that is required reading for anyone obsessed with Ridley Scott’s bleak vision. But, like its subject, it could have been even greater. It could have brought in criticism of the film. It could have better pondered the ever-broadening cult interest in the film, as well as the movie’s extensive influence on science fiction. It could have dealt with the film’s source novel, Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, in more depth. Those criticisms aside, this is a fine work, one to be treasured along with the film. In the end, Paul Sammon’s eye is precise and penetrating.