The Hitchcock Conversations is an ongoing project between me and James W. Powell, in which we study Alfred Hitchcock’s filmography in chronological order. I’ll be publishing one conversation per week.

The Hitchcock Conversations is an ongoing project between me and James W. Powell, in which we study Alfred Hitchcock’s filmography in chronological order. I’ll be publishing one conversation per week.

(By necessity, spoilers ahead!)

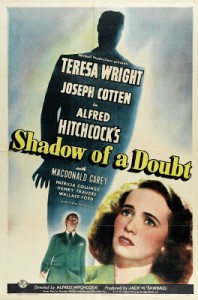

Synopsis: Charlotte ‘Charlie’ Newton is bored with her quiet life in her small town. She wishes for something exciting to happen and knows exactly what she needs: a visit from her sophisticated and much traveled uncle Charlie Oakley, her mother’s younger brother. Imagine her delight when, out of the blue, he comes to town. But soon young Charlie begins to notice some odd behavior on his part, such as cutting out a story in the local paper about a man who marries and then murders rich widows. When two strangers appear asking questions about him, she begins to imagine the worse about her dearly beloved uncle Charlie.

James: Shadow of a Doubt is one of my favorite Hitchcock films, but it’s fallen off just slightly. It’s still in the top three of what we’ve seen so far, don’t get me wrong, but I found some things that didn’t work for me on this, my fifth viewing. Actually, it’s just one thing, and I’m going to start by talking about it, then I’ll get to all the things I liked. The only real problem I had with this film is that it’s too obvious that Uncle Charlie (Joseph Cotten) is indeed a killer. For me, as a viewer, there was no doubt. He’s guilty—plain and simple. There are just too many clues pointing to him: Even the opening sequence shows that he has something to hide. There’s his monologue at the dinner table about “fat, silly women,” and there’s the fact that he’s watching as his niece Charlie (Teresa Wright) falls on the back stairs. There are many others, but you get the point. Sure, in the beginning there’s doubt, but I feel this film would’ve been better had his guilt been doubtful right up to the end on the train. Even had the film focused more on the other suspect, on the run on the east coast, maybe had Hitch shown that he was just as strong a suspect as Uncle Charlie, I might have felt more doubt. (Granted, this is the fifth viewing, and I believe I doubted longer in the first viewing.)

Jason: I love this flick. I’ve also seen it a few times, and this time I appreciated it more than all the other times (thanks to our little project). Which is interesting, since you say it’s fallen off slightly for you. And although I see where you’re coming from with your complaint, I don’t think I agree with it. I think it works in the film’s favor—in fact, it’s probably essential—that we know Uncle Charlie is guilty. He even has a voice-over line at the start, when he’s watching those detectives contemptuously, that pretty much states his guilt: “What do you know? You’ve got nothing on me.” I think the whole point of the film is that the “doubt” of the title is in young Charlie’s mind, and her complete turnaround from idolizing her uncle to wanting to murder him herself.

Jason: I love this flick. I’ve also seen it a few times, and this time I appreciated it more than all the other times (thanks to our little project). Which is interesting, since you say it’s fallen off slightly for you. And although I see where you’re coming from with your complaint, I don’t think I agree with it. I think it works in the film’s favor—in fact, it’s probably essential—that we know Uncle Charlie is guilty. He even has a voice-over line at the start, when he’s watching those detectives contemptuously, that pretty much states his guilt: “What do you know? You’ve got nothing on me.” I think the whole point of the film is that the “doubt” of the title is in young Charlie’s mind, and her complete turnaround from idolizing her uncle to wanting to murder him herself.

James: I see your point about the key of this film being the growing doubt in young Charlie’s mind. And I agree that knowing Uncle Charlie’s guilt isn’t necessarily a bad thing. But now that I think further on it, maybe it’s the fact that young Charlie gives in so easily. Or that Uncle Charlie doesn’t have the answers for her to explain this or that away. Now, don’t get me wrong. This issue for me is only the difference between an A+ and an A or an A and an A-. A perfect film compared to a nearly perfect film. It’s almost not worth noting. But I do wish some elements were expanded or used more.

Jason: Examples?

James: Well, for example, when the door to the garage shuts on the young couple—young Charlie and Detective Jack Graham (Macdonald Carey)—it could be Uncle Charlie’s doing, but it could also just be the wind. I loved the notion that the girl could always be walking that fine line between thinking he’s a good guy or he’s a murderer. I guess I just wanted more of that. I still think it would’ve been nice to have my own doubt, but I think it would’ve been more powerful if Charlie wasn’t sure even up to the end. Maybe she doubted herself even though the clues matched? Or maybe there was “proof” that Uncle Charlie did not do it? Perhaps what I’m saying is that I wanted her doubt to grow and grow. Instead, it felt just a little too abrupt. Not as abrupt as the romance in some of Hitch’s movies, but a little too clean, too fast for me. One thing that made Rebecca take the top spot for me was the subtle growth of the main character. I wish Charlie grew at a similar pace.

Jason: You remind me of a quote in a Peter Bogdonavich interview with Hitch. Bogdonavich says, “Young Charlie makes a lot out of the fact that she and her uncle are similar, and yet she’s the most eager to suspect him of the worst.” Hitch’s answer is that she’s the one looking most closely at him, but I think there’s a lot more there. Being his psychic twin, she catches on to his evil because deep, deep down, she understands it. I would say it even runs in the family. So when she immediately suspects him, I bought it. But I see where you’re coming from, that Hitch could have made his guilt less obvious. But I think you’re talking about a different film. I think Hitch wasn’t really interested in casting doubt in our minds, just in Uncle Charlie trying to shield the truth from his niece, who knows him better than he thinks she does.

James: You’re closer to getting me on your side with the whole “both Charlies are the same person” kind of talk, combined with what Hitch said, but it still didn’t quite work for me. I understand that we’re not the ones who should feel the doubt in our minds, but I still think it should have grown more with the younger Charlie. The funny thing is that I didn’t have a single problem with this film until this viewing. It’s possible that I’ve either seen it too many times, or that I’m looking much more closely during this tour of Hitchcock’s films.

Jason: What I took most from this film is the way the Charlies are psychically linked. It’s spelled out plainly at the beginning as a kind of telepathy, and it’s a real kick to watch how that develops throughout. I love young Charlie’s opening words about her family: “This family’s gone to pieces. We’re in a terrible rut.” Her father brings up money, and she says, “I’m talking about souls!” She’s obviously very sharp, with a little cynicism. But mostly she’s this buoyant, happy, small-town family girl. And we meet Uncle Charlie, who’s this dark, brooding creep. So watching them come together is fascinating. He backs off from the villainous personality we see in New Jersey and goes into small-town mode, all charming and happy, and at the same time, young Charlie starts to doubt him, and the darker side of her personality comes out, as if they really are two sides of the same coin. This is definitely the most interesting aspect of this film for me.

Jason: What I took most from this film is the way the Charlies are psychically linked. It’s spelled out plainly at the beginning as a kind of telepathy, and it’s a real kick to watch how that develops throughout. I love young Charlie’s opening words about her family: “This family’s gone to pieces. We’re in a terrible rut.” Her father brings up money, and she says, “I’m talking about souls!” She’s obviously very sharp, with a little cynicism. But mostly she’s this buoyant, happy, small-town family girl. And we meet Uncle Charlie, who’s this dark, brooding creep. So watching them come together is fascinating. He backs off from the villainous personality we see in New Jersey and goes into small-town mode, all charming and happy, and at the same time, young Charlie starts to doubt him, and the darker side of her personality comes out, as if they really are two sides of the same coin. This is definitely the most interesting aspect of this film for me.

James: The most telling scene about these two being “twins” and of her darker side coming out is when she confronts Uncle Charlie late in the film and says, “Go away or I’ll kill you myself.” For that brief instant, it’s almost as if she’s become her uncle. She’s completely gone over to his way of thinking.

Jason: Yes, that “Go away” line is so great, it gives me chills . . . the fact that she’s as capable of murder as he is, despite her youth and innocence. It’s a complete role reversal for her, another abrupt jump—from doubt to full-on murderous rage—that works for me. Along these lines, I was really impressed by one particular shot: The Charlies learn together that the other suspect in the murders has been killed back east, and Uncle Charlie walks happily away, whistling, walking up the stairs, and he pauses to look down at backlit, virginal Charlie in the doorway, staring up at him, and it’s at that moment when we know the rest of the story is between just them. I just found that moment really powerful. I must admit to being actually surprised when he starts actively trying to kill Charlie. And of course, one of the methods is a broken stairway.

James: As you know, I’ve always loved the fact that the bad guys in Hitch’s films can be good and/or civil . . . even likable. And here, the little naïve girl turns into someone who can be evil and unlikable. Very effective. Particularly since, as you said, it’s all spelled out in the very beginning.

Jason: I did some reading about this film last night and came away flabbergasted by the film’s constant accumulation of doubling, things presented in pairs. Of course, all these instances refer to the two sides of the human personality embodied by Uncle Charlie and young Charlie—the negative, murderous, decadent side contrasted with the positive, innocent, optimistic, generous, good, loving side. The “twos” come fast and hard: two detectives, two criminals, two dinner sequences, two toasts, two amateur sleuths, two railway sequences, two scenes in the garage, two double brandies ordered at the Till Two bar (served by a waitress who’s worked there two weeks), two attempts to kill young Charlie, two converging sets of train rails at the climax . . .

James: Wow, that’s a lot of twos. Very cool, indeed.

Jason: And there are many more. I suddenly feel the need to watch this film again.

James: I loved the whole “danger in a small town” thing. You’re right to say that Wilder had a huge part in this film because it’s obvious that the writer knew about living in a small town. The fact that everyone is oblivious to what’s going on—except the girl, of course. In a town where no one locks their doors, and where there’s a traffic officer who knows your name, and where families invite strangers in to do interviews . . . suddenly here’s all this deception and danger and no one knows. Great stuff.

Jason: Yes, the small-town element feels perfect, thanks to Wilder. And one thing I hadn’t really paid attention to before was how Santa Rosa is contrasted with the slums of New Jersey, where the movie starts. I actually replayed the first 10 minutes to soak it all in. We get the same camera movements in each section, from wide establishing shots to closer shots of the buildings to move-ins on the central characters—both Charlies in the exact same position, brooding on their respective beds. It’s really an amazing setup of settings and of the concept that these two people are spiritual twins. “We’re twins!” they both say later, and I think the whole meaning of the film is in that line and foreshadowed in these opening scenes. And of course, they share the same name.

James: I thought Cotten did a great job as Uncle Charlie. He played the “perfect brother” part of the role very well, yet there was something dark about him. He could be both innocent and menacing.

James: I thought Cotten did a great job as Uncle Charlie. He played the “perfect brother” part of the role very well, yet there was something dark about him. He could be both innocent and menacing.

Jason: Joseph Cotten was perfect in the lead role. And unless I’m mistaken, this is the first time the main character in a Hitch film is a villain. (Cary Grant would count in the originally intended version of Suspicion, but not as the film was released theatrically. And later, we’ll get Anthony Perkins in Psycho.) One of the great things about the Uncle Charlie character is that he’s charming and idolized while being a terrible human being. Cotten played that well, and as young Charlie gradually learns more and more about him, the audience almost feels bad for thinking well of Uncle Charlie early on.

James: And I liked the fact that we as the audience could see that he was the killer and that he brought trouble to this small town, but no one else could. While I never thought the family was in danger (except for young Charlie), it was still interesting because of how the mother—Emma Newton (Patricia Collinge)—would react to such accusations.

Jason: Does young Charlie remind you of the Erica character in Young and Innocent?

James: Interesting comparison. I hadn’t considered that, but yeah, it’s a good match.

Jason: She’s a similar Nancy Drew character, uncovering a mystery and coming of age at the same time.

James: Speaking of young Charlie, I loved the library scene. After she reads the article that damns Uncle Charlie, the camera pulls back and up. The library suddenly seems so big and dark, while she seems so small and alone. In those few frames, we feel what she’s going through. It’s as if a huge dark cloud has fallen over this happy little town. It’s a very powerful scene. It reminded me of Rebecca, and how Hitch was able to portray the girl’s loneliness. Shadows and a huge room play a key role in that film, and it plays a role here. This is obviously where the story turns into more suspicion and doubt and where there’s more danger and tension, but it’s also the scene in which little naïve Charlie grows up.

Jason: The library scene is probably the most effective single scene in the film. It’s pitched perfectly, such a huge character moment, and every angle and sound is right on. The whole race to get there on time, and pleading with that cadaverous librarian for just a few minutes, topped by the discovery of the article, and the way the soundtrack explodes with drama as we pan down the article. And just when you think the scene has reached its dramatic peak, Charlie removes the seemingly stolen ring that Charlie has given her and looks at the initials, which match those of one of the victims. I was blown away, for those reasons and the ones you mention. Just a classic scene.

James: Also, stairs play a big role in this film. Not only does Charlie fall and hurt herself on the back stairs, but there’s also that great shot of Uncle Charlie at the top of the stairs, with shadows on the ceiling, making him stand out and look very menacing.

Jason: The film is filled with stairs and stairwells. Knowing what we know, the stairs and accompanying moody shadows give the film a terrific sense of suspense. You mention the shots of Uncle Charlie at the top of the stairs, and that reminds me that I thought a few times of The Lodger. There are at least three moments that reminded me of that film: First, when Uncle Charlie first comes to stay, and he examines a picture on the wall, checks out the room. Second, as you say, the multiple shots of Uncle Charlie peeking mysteriously down the stairwell. Third, the shots of him pacing in his room as things get more doubtful for him.

James: I hadn’t thought of The Lodger, but that’s a good comparison too. It’s a very similar plot, if you think about it. In the earlier film, everyone thinks the lodger is the killer. Here, one character grows to think that same thing. Hmmmm, that makes these two films good companion pieces. Interesting.

Jason: I also got a kick out of another possible homage: young Charlie walking up the shadowed stairs to bring her uncle a glass of water on a tray. Shades of Suspicion.

James: Did you notice how Hitch was able to move in and out of the house? The camera moved in and out of that front door rather effectively. It was as if we the viewers, complete strangers to this family, were invited to see the dynamics of this otherwise “normal” family. It heightened that feeling that we were viewing something that would normally remain behind closed doors.

Jason: Interesting observation. And it didn’t feel like a set, either. It felt like a perfectly natural suburban home. I did notice many instances of the camera on the move, but the movement through the house was so natural that I didn’t really pay much attention to it. But in retrospect, you’re right. Very effective. One of the great things about this film is that finally we have a Hitch flick that was shot mostly on location, which gives it a very naturalistic feel, as opposed to the artificiality of rear-projection process shots. Apparently, Fox (who “borrowed” Hitch from Selznick) had put a cap on set-construction funds, and so Hitch was basically forced out of the confines of the studio. The result was that he loved the experience because it reminded him of his early silent days.

James: When we finally get into the Newton house, did you notice the lack of communication between the family members in the scene where everyone is introduced? That reminded me of Hitch’s fascination with troubled couples. It wasn’t infidelity, but it was as if this was the next step in family life.

Jason: I noticed it too, especially on the part of young Ann Newton (Edna May Wonacott), who seemed misunderstood throughout. I wouldn’t say she was the best child actress in the world (apparently she was plucked right off the streets of Santa Rosa for the role), but she definitely had personality. And I liked how the father—Roger Newton (Charles Bates)—always seems lost in his own little world of crime stories and modus operandi with his bumbling friend Herbie Hawkins (Hume Cronyn). They’re so wrapped up in fantasy that they’re clueless to the real criminal in their midst.

James: What did you think of those talks? You point out that the characters are blind to the criminal in their midst, but you didn’t really say what you thought. I liked it. It served as a sort of comedy relief, but it tied in with the larger story, which I appreciated. I loved the scene in which young Charlie blows up at them and the dad says, “We’re not talking about killing anyone. He’s talking about killing me. And I’m talking about killing him.” Great stuff. The whole idea of them talking about possible murders reminded me of Suspicion, but here, it’s obviously more lighthearted. At the same time, however, it adds to the sense of foreboding and doubt, just as it did in the earlier film.

Jason: I really liked those crime-story interludes with dad and Herb, for all the reasons you mentioned. I also caught the Suspicion reference.

James: In the scene in which young Charlie goes out with the detective . . . what did you think of that jump from them laughing and having a good time to her saying, “Oh, you’re a detective and you’re looking into Uncle Charlie.” That seemed a bit quick for me. Granted, we don’t see their dinner or their walk, but the cut is very sharp. I thought, “Wait a minute. How did she make that leap so fast?”

Jason: I did notice that cut, and you’re right, it’s a little fast. It does seem that we’re missing a little conversation there. But it didn’t bother me too much. I guess I was more bothered by the fact that this older guy, seemingly 30 or so, is prowling after a 17-year-old. (That’s how old I’m guessing they are.) The age difference reminded me, again, of Young and Innocent.

James: Yeah, he’s too old, for sure . . . or she’s too young . . . that struck me as all wrong. But speaking of the romance, I appreciated that the two would-be lovers don’t jump the gun. The scene in the garage is well played.

Jason: Agreed that the budding romance is subtle. I like that they’re just barely holding hands at the end, almost as if they’re feeling ashamed by everything that’s happened and reluctant to hold any feelings of love.

James: I liked that they don’t exactly pronounce their love in that scene and that they don’t get married during this whole film.

Jason: I just learned that Teresa Wright recently died. Very eerie. Her death is making me reflect on her performance in the film, and you know, it was really quite amazing, how she goes from an openhearted, innocent girl to a disheartened, almost world-weary adult, capable of murder, by the end of the movie. We talked about Joseph Cotten, but Wright turned in an A-grade performance.

James: I don’t know, that performance by Fontaine in Rebecca outweighed pretty much any performance before or since. By the way, I think she died on Sunday (March 6, 2005)—which is weird, because we might have been watching the film just as she passed. There’s something poetic about that if it’s the case.

Jason: She was an Academy Award winner, and she seemed to be a top-notch person, from what I saw in that featurette. Anyway, a toast to her.

James: What did you think of Uncle Charlie’s monologue at the dinner table?

Jason: Uncle Charlie’s soliloquy is a great moment—“faded, fat, greedy women”—and maybe a peek at his unraveling in Santa Rosa. At first you might think he’s going to get away with his crimes and remain with his family for the long term, as he even suggests at one point, but then his darker impulses start peeking out from under the surface. It’s a great, foreboding moment. And yeah, incredibly dark for the time.

James: Even by today’s standards it was one hell of a dark way to voice one’s opinions. There’s no beating around the bush. It was startling and refreshing. I wonder what audiences of the 1940s thought.

Jason: Another thing I learned from one of the books is that the opening—Uncle Charlie lying in bed as two men search for him—is a nod to Hemingway’s The Killers, which I subconsciously recognized but didn’t acknowledge.

James: I need to get The Killers. I think I’d like that one.

Jason: You can probably read The Killers online somewhere.

James: Oh, I don’t want to read it. I want to watch it.

Jason: The movies are really nothing like the original story.

James: Anyway, back to Shadow of a Doubt. Did you notice all the smoke? The smokestack on the train, Uncle Charlie always smoking, the fumes from the car in the garage? I’m not sure if it was intended or not, but there seemed to be smoke all over the place.

James: Anyway, back to Shadow of a Doubt. Did you notice all the smoke? The smokestack on the train, Uncle Charlie always smoking, the fumes from the car in the garage? I’m not sure if it was intended or not, but there seemed to be smoke all over the place.

Jason: I definitely noticed the black smoke of the train approaching Santa Rosa, an obvious feeling of foreboding as the bad guy arrives in town. That was great, combined with powerful train imagery, both sight and sound. I noticed all the smoke instances, too, as when Uncle Charlie blows that perfect smoke ring (reminding us of the ring he put on young Charlie’s finger?), and he’s constantly smoking. And as you say, there’s the smoke from the car. I chalked it all up to the “smoke of subterfuge,” the notion that the truth is foggy and inscrutable, or that evil has come to clear-eyed Santa Rosa in a rush of smoke.

James: Nice.

Jason: What did you think of the ballroom-dancing title sequence, and the recurrence of the imagery throughout? At first I thought it was extremely odd, but of course it becomes clear with the revelation of the name of the waltz (which “jumps head to head”). But it’s still kind of odd, stuck in there. It didn’t feel like a perfect fit. Maybe the images would have worked better if we knew he targeted ballroom events like that for his “merry widows.” Which reminds me, I loved the subtlety of the shot of Charlie on the train at the end, looking toward what appears to be his next victim.

James: I didn’t really like those ballroom shots. Sure, by the end we understand them, but those few early shots just didn’t seem to work. It would’ve worked if your thoughts were taken into account and we knew up front that he targeted certain people. But you know what? Hitch loves ballrooms. How many films have we seen with a ballroom scene? A handful at least.

Jason: Yeah, what is the appeal of those ballrooms? I know they’ll appear in still more of his films. I guess Hitch was just a sucker for high society, which also speaks to his desire to have the most handsome, debonair leading men and the classiest, most gorgeous women as his stars. A large part of his filmmaking, I think, was acting out his fantasies. Hitch was very self-conscious about his appearance, especially his weight, so maybe this can be chalked up to a kind of wish fulfillment, same as the high-society nature of many of his other films.

James: Ah, interesting. I never thought about that. It seems a bit far-fetched, though. At least, at first. I mean, all of Hollywood cast those actors. Beauty and good looks have always played a key role, so I don’t think his weight was a huge motivational factor. Sure, it could have played a part, and I could see how his films could be a fantasy (“I wish I were this rugged good-looking man on an adventure”), but I would assume that would be a deep, deep psychological thing that never came to the surface.

Jason: Speaking of the fat man, I really liked the Hitch cameo in this one—his back to us while he’s holding a handful of spades at a card game on the train.

James: What game were they playing that he’d have a hand full of spades?

Jason: I doubt it was a real game, just a joke.

James: The documentary pointed out something I find interesting, and that is Hitch’s use of the smart little girl and the typical boy in his families. It’s so true. The boy is always a little troublesome tyke, and the girls are always intelligent and often factor into the plot as they help in some way or another in “solving” the case.

Jason: I liked that part of the doc, too. Most of the “daughters” wear glasses and are very smart. The young daughter in this one, Ann, is immediately suspicious of Uncle Charlie even if she can’t pinpoint why.

James: Anyway, to wrap up, this film is refreshing because it’s so different from the Hitch films that have come before, yet it shares many of the themes. I think you said last week that the “wrong man accused” storyline was getting old, and in a way, it is. So it’s nice to have a little change of pace here while still maintaining that edge.

Jason: You’re right, Shadow of a Doubt is very different from his other films, and in fact it’s the first film to really take a good hard look at America and American values. Sure, Foreign Correspondent has a really American feel, as far as patriotism and propaganda, but in the end, it’s more of an international film. Shadow of a Doubt feels quintessentially American.

James: Yeah, this is the first film that sets Hitch apart from his earlier days. It’s an American cast set in an American town. This is the first film he’s done that doesn’t feel foreign in any way, shape, or form. I agree with your thoughts about shooting on location. I also think that Wilder was a huge player in that whole feeling too.

Jason: Shadow of a Doubt is definitely at the top of my list so far. I like how the documentary on the DVD calls the film a “troubling, ambiguous character study.” I feel like I could watch this one endlessly and still come away with new insight. As a study of the yin and yang of human behavior, it is thoroughly engaging and rewarding. I can understand why Hitch often called this his favorite film.

James: Rebecca is still my favorite. Shadow of a Doubt remains a close second with The 39 Steps. It’s definitely a great movie with much more underneath the surface. I can see why this is a personal favorite of his. It hits on so many levels, and it’s a little different from what he’s done both before and after.

Great discussion about a great film. There was a typo though. You say Charlie’s father is played by Charles Bates when that should be Henry Travers.

The card game Hitch is playing is Bridge. And 13 spades would be unbeatable assuming he has the sense to bid “7 spades”. That’s why he doesn’t look to we’ll according to the other players. Shock at the hand he has been dealt. Of course, he is also playing a very dark hand.