The Hitchcock Conversations is an ongoing project between me and James W. Powell, in which we study Alfred Hitchcock’s filmography in chronological order. I’ll be publishing one conversation per week.

The Hitchcock Conversations is an ongoing project between me and James W. Powell, in which we study Alfred Hitchcock’s filmography in chronological order. I’ll be publishing one conversation per week.

(By necessity, spoilers ahead!)

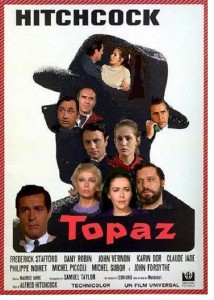

Synopsis: A high-ranking Russian official defects to the United States, where he is interviewed by a US agent. The defector reveals that a French spy ring codenamed “Topaz” has been passing NATO secrets to the Russians. Michael calls in his French friend and counterpart Andre Devereaux to expose the spies.

James: Overall, I liked Topaz. It’s more of a straightforward thriller, which I wasn’t expecting, but I ended up really being sucked into the story. I wouldn’t say the film has any spectacular scenes, but it has a nice, slow pace with just enough mystery and suspense to keep it going. The ending is rather dull, though. I was hoping for something much more climactic. But that doesn’t make Topaz a terrible movie—just one that doesn’t end well.

Jason: I’m with you that the film starts out in an intriguing way. I wanted to give this film every benefit of the doubt. But at a certain point about halfway through, I found my interest waning, and by the third act, I really didn’t care how anything was going to resolve. To me, there’s just way too much going on in this film—too many characters, too many subplots, too many betrayals, too many scenes. It’s another very long film that wears out its welcome, and I detected very few signature Hitchcock touches. No, I didn’t care for Topaz. Hitch just doesn’t seem to be all that interested in the story he’s telling.

James: I agree with you on most of your points, but maybe my initially low expectations helped me get into this one, despite its shortcomings. Then again, maybe this time I was able to get more involved with the story itself, rather than the film as a whole. Does that make sense? A lot of Hitchcock’s films are good because the film as a whole hits on all cylinders. For me, Topaz works simply because the story is good, not because of the filmmaking.

Jason: There are moments that I liked, and we’ll get to those. But overall, nope. The film is just too complex and dated. It’s as if Hitch had an idea for a MacGuffin and instead of letting it fall to the side, as any good MacGuffin should do, he focused all his energies on it and made it the center of the film! As a result, all the potentially interesting aspects of Topaz fall to the side, and we end up not caring about the characters and their passions and motivations. We’re left with the rather cold machinations of the plot. Boring!

James: See, I didn’t mind that the film was more plot-driven than usual. I think this is a decent film, just not a great Hitchcock film. I actually found myself watching Topaz as if some no-name director was in charge. I had no problem with that. But I will admit that it’s sad to see such a great filmmaker start to slide.

Jason: To me, just hearing you say, “I found myself watching Topaz as if some no-name director was in charge,” is just sad. I guess that’s my main problem with this film. It’s anonymous. It’s not a Hitchcock film.

Jason: To me, just hearing you say, “I found myself watching Topaz as if some no-name director was in charge,” is just sad. I guess that’s my main problem with this film. It’s anonymous. It’s not a Hitchcock film.

James: Perhaps my favorite aspect of the film is how the story unfolds. We’re first involved with a high Russian intelligence officer—Boris Kusenov (Per-Axel Arosenius)—who’s defecting to the United States, and you think Topaz will be all about him. Then we meet CIA agent Michael Nordstrom (John Forsythe), and it’s suddenly his story. Then, we get the French operative, Andre Devereaux (Frederick Stafford), and here’s where we finally get to the meat of the story. Andre is the main character. I like the way the film hops from one character to the next. We can discuss this in more detail as we work through the film, but in general, I like the way that works.

Jason: I would have liked the film’s rambling structure a little better if I’d cared about Andre. (Or any of the characters, for that matter.) But he’s just not very interesting. The actor is quite wooden, and Andre just bounces from one place to another, with little excitement. And when we find out that he’s cheating on his wife, betraying his family, and baldly lying to them about his involvement with resistance leader Juanita de Cordoba (Karin Dor), well, I just lost any sympathy for him. He’s probably my least favorite main character in any Hitch flick that I can remember.

James: On a side note, as far as the filmmaking is concerned: This film is in desperate need of a better editing job. How many times does the camera extend a scene beyond its worth? Too often.

Jason: Good point. It seems as if Hitch could have sliced 20 minutes of padding from the film and at least brought the movie to a more acceptable two-hour length. I mean, parts of this movie seem interminable.

James: To get started on the progression of the film, I want to point out that the opening is nearly worthless. Why the heck would Hitchcock use a crane shot to show the Kusenov family leave their house? It’s so overkill! Pointless. The shot really serves no purpose and sticks out like a sore thumb. If nothing else, it just prolongs the opening and slows it to a crawl. Not a good idea. Once the family starts being “chased” by Commie thugs, we realize we’re in for a ride, but those first few minutes are terribly done.

Jason: I completely agree. This shot is the first time I’ve really felt that Hitchcock is becoming sort of a parody of himself. Before, these kinds of shots had a point within the context of the film’s plot or theme or mood, but this one has no meaning. It’s just a complex shot for the sake of gimmickry. Too bad.

James: The whole chase sequence at the beginning is both tense and too slow. I was sitting there, actually fairly riveted, but at the same time, I kept thinking that it had better pick up soon. I think the action of the scene, in which the family runs to the car and the daughter, Tamara (Tina Hedstrom), slams into a passing bicyclist (whooopie), could have been elevated and trimmed, but it did the job.

Jason: Okay, I’m pretty much with you in the film’s early scenes. I like that we have to piece together what’s going on. I liked seeing these thugs follow the Kusenov family into that porcelain craft factory, and I liked the way Tamara escapes by breaking a piece of the porcelain. Best of all, almost all of these opening 15 minutes are silent, so Hitch seems assured at this point. That craft breaking on the ground is quite jarring. But the scene with Tamara crashing into the bike is overbaked, and it’s another moment that made me think, Uh oh, maybe Hitch isn’t at the top of his game.

James: After Nordstrom rescues the family, avoiding an assassination attempt, I like that Boris is sort of an ass on the airplane, pointing out that he would’ve performed the rescue differently.

James: After Nordstrom rescues the family, avoiding an assassination attempt, I like that Boris is sort of an ass on the airplane, pointing out that he would’ve performed the rescue differently.

Jason: Yeah, Boris comes across as a jerk to Nordstrom on the plane. It’s cool how we develop a certain impression of Boris in the silent scenes with his family, seeing that he’s trying to protect them from the thugs, and when we finally hear him talk, he’s an ass. Nice misdirection.

James: Yep.

Jason: You know, it’s nice to see John Forsythe return to a Hitch film (after playing the lead in The Trouble with Harry 14 years earlier), but he’s not nearly as interesting a character in this film, although he could have been.

James: Nordstrom never really jumps off the screen, does he? I wouldn’t say he’s underused or anything, just not that vibrant.

Jason: Right, and the tough thing to swallow is that Nordstrom could have been a key character here. Hitch could have really developed some kind of fascinating back story with him. I like the way Nordstrom keeps popping up in places unexpected. Explore that! What’s his past relationship with Andre’s wife? What’s his mystery? No, there’s nothing like that to this character. He’s just a government stooge who needs constant favors from people, particularly Andre.

James: So, once Boris makes it to America, the CIA interrogates him to find out what he knows. Yet, he’s not expecting to be grilled like this. I liked this aspect of the film because we’re not sure who the good guys are. We assume the CIA guys are, but are they being unfair to him? It’s hard to say at this point.

Jason: Yeah, this is about when we find out that “Topaz” is a code word for some kind of Cold War secret involving Cuba. The CIA really wants some information out of Boris, but he’s not really in the talking mood. You’re right, it’s ambiguous who the good guys are. But even though Hitch throws in that ambiguity, the politics of the film are very clear: This is another anti-Communist tract, as was Torn Curtain, but it’s nice to see that even the good guys can be assholes.

James: And this is also when we meet Andre Devereaux, who also isn’t what he seems. At first, I thought he would turn out to be the villain, but as we’ve said, he actually becomes our main protagonist. While I think this “who’s who” type of thing hurts the emotion of the film, I still like that it adds to the mystery.

Jason: Andre’s introduction is a bit maddening. I hated his wife, Nicole (Dany Robin). She’s this brittle, difficult-to-understand French woman, and worse, Robin, the actress portraying her, is awful—wooden and shrill and false. Knowing that Andre would marry her made me like him less. Hahaha.

James: I was actually expecting his wife, or maybe his daughter, Michele (Claude Jade), to turn out to be the head of Topaz. Or maybe Michele’s husband, Francois Picard (Michel Subor), the journalist. Someone. But no, that’s not how it turns out. Anyway, I do like the unspoken relationship between Andre and Nordstrom, even though it’s underdeveloped.

Jason: Yes, the camaraderie between Nordstrom and Andre is intriguing. They seem to share an interesting history, as if they’ve done many covert operations together as spies from different countries working for the common good. I liked the scene in which it becomes clear, finally, where this movie is going: Nordstrom wants Andre (who, again, is a Frenchman) to gather secret information from a Cuban named Luis Uribe (Don Randolph), who would never deal with the CIA because he hates all Americans. This is a fairly interesting setup, I must admit. And again, at this point, I’m in tune with the film and getting some enjoyment from it. I’ll let you know when Topaz turns sour for me.

James: Hahaha. Sounds like it already has! But okay, I totally got into the scene in which Andre goes to the florist, Philippe Dubois (Roscoe Lee Brown), and asks him to go undercover to gather the information he needs from Uribe, who happens to be in New York. The entire sequence is very well played. There’s even a bit of humor when Philippe wonders whether he should pretend to be a journalist from Ebony or Playboy. I just think these scenes are fun and exciting. Seems that sense of fun is missing from some of these later Hitch films.

Jason: This is probably the best part of the film, before it gets too big and plot-heavy. This florist, Philippe, is a good character, willing to help out Andre at great risk to himself, and able to play a dangerous role without much prompting. He also seems to have a great sense of humor. What did you think of the expository scene between Andre and Philippe inside the greenhouse? Hitch plays it completely silent, simply because we don’t really need that information—we already know it. The scene reminded me of the sequence in North by Northwest when “the professor” fills Roger Thornhill in on back story while a plane revs over his dialog, drowning it out. But, you know, in Topaz, this similar scene seems a bit overdone. The actors’ gestures are too obvious. Andre takes from his jacket the envelope of cash that he will pay Philippe for this job and points at it emphatically, all for the benefit of the audience. Know what I mean? I can understand Hitch’s intent here, but he overdoes it! Similarly, in the scene in which Philippe gains access to Uribe at the hotel, Uribe and Philippe share a silent scene out on the street while Andre watches from a safe distance. But again, their gestures and movements seem overly false to me—lots of pointing and dramatic gesturing. Did you feel this way? This is another instance, to me, of Hitch becoming a parody of himself. And when Philippe gets Uribe to agree to take him inside to meet Castro’s right-hand man, Rico Parra (John Vernon)—for the purpose of stealing some secrets from a red (i.e., Commie) attaché case—he looks across the street, makes an obvious gesture at his watch and holds up his hand: “Five minutes!” It’s silent, but it felt like he was yelling! And Andre smiles and nods from across the street. Anyone watching them would’ve said, “Hey, they’re communicating a secret code! Get ’em!”

James: Hahaha. I didn’t think about this stuff as negatively as you did, but I certainly had some problems with the silent scenes. You’re right, there’s too much gesturing. It isn’t subtle at all. When Andre is across the street watching, I thought they’d certainly get caught because of all the gesturing and pointing.

Jason: What did you think of the scene in Parra’s room, when Philippe pretends to photograph Parra on the balcony while Uribe steals the briefcase? To me, it’s yet another scene where elderly Hitch goes just a bit too far. The shots of Uribe reaching for the case go on for an eternity, and the result seems kind of silly. Hitch is trying to draw out the suspense, but I was just laughing, saying, “Come on!”

James: I totally agree. Some of these “suspenseful” shots take a long, long time. But I don’t know why it doesn’t work. I mean, Hitch has done these things hundreds of times before, and this is the first time it’s really stood out and felt off. Why is that?

Jason: I think, as we’ve said, that Hitch is just no longer at the top of his game. He’s falling back on some old tricks and not getting them quite right.

James: Maybe.

Jason: What did you think of John Vernon as Parra? Did you recognize him? He played the dean in Animal House.

James: I did recognize him. I thought he played the Parra role very well, very menacing, although I knew he wasn’t Cuban. Hahaha. He does some voices in the Batman cartoons, too.

Jason: Did you notice that to get to Uribe’s room, Philippe goes into an elevator, but actually Uribe’s room is on the same floor as Parra’s? That was confusing.

James: I was a little confused there, too. I think they’re on the same floor, but there’s an editing problem involving that elevator. This may come completely out of the blue, but after Parra sees that his case is gone and goes to confront Uribe, I thought there was a touch of sexual connotations when Parra bursts in on Philippe and Uribe. It’s as if the two men are caught in some compromising position. I don’t know what it is about this scene, but I immediately thought that they’d been caught with their pants down.

Jason: So, yeah, the scene in which Parra and his henchman burst in on Uribe and Philippe—I didn’t think of the gay-sex angle, but I can see it. And after Philippe scoots out the window, I love the withering stare that Parra gives Uribe. You just know that dude is dead.

James: I like the fact that Philippe has to dive out the window to escape. That’s a nice touch, and it reminded me of Foreign Correspondent, in which Hitchcock used a dummy in a fall from a window.

Jason: Nice catch!

James: Also nicely done was the way Parra’s henchman runs straight into Andre on the street. Still, I think it’s silly that Philippe wouldn’t just run back to the flower shop instead of slamming into Andre and handing off the camera in front of everyone. Seems that a later handoff would’ve been a safer idea.

Jason: I liked this chase scene, to a certain extent. I agree with you about Philippe handing Andre the camera, but I really liked the way Philippe just returns calmly to the flower shop and starts working on a flower arrangement. As if he’s been a part of these kinds of chases thousands of times. (By the way, this film really has a preoccupation with flowers.)

James: The shot of Philippe returning to the flower shop is brilliant. I like how he’s so calm about it, especially since he’s suddenly putting the final touches on a floral cross for a funeral—essentially, Uribe’s funeral. Good stuff, indeed.

Jason: So, now the film changes gears suddenly, and it’s at this point that Topaz starts really losing me. We get an out-of-the-blue scene between Andre and his wife, Nicole, in which she tearfully accuses him of being unfaithful, just as he’s about to fly to Cuba. She suspects him of an affair with Juanita de Cordoba, the leader of an underground resistance network in Cuba. Andre vehemently denies the affair, but then he immediately gets on a plane, goes straight to Juanita, and they dive right into the hot-and-heavy sex all over her palace. I mean, I don’t really care for Nicole, but what a prick!

James: Wow, I didn’t mind that at all. I think the problem is that the film takes so long to get here. To me, this is the emotional crux of the whole film. The MacGuffin sets us up to see how these two lovers interact. The fact that Andre doesn’t run off to Juanita until an hour into the film does make it less appealing and less powerful because, by now, we think Topaz is solely a typical thriller. Does that make sense? If you make the Andre-Juanita relationship the focal point of the film—just as romance ends up being the centerpoint of most of Hitch’s films—you have a stronger emotional tie. As it is, it still works for me. It works on a story level, just not at an overly emotional level.

Jason: I see what you’re getting at, and I tried to view it that way, but there’s just not enough here. Not only do we arrive at this relationship completely out of the blue, in the middle of the film, but once Juanita’s little story arc is finished (ending with her death), she’s pretty much forgotten, right? I guess you could say that she sacrifices herself for Andre’s cause, but you’re right, there’s just no real emotional heft here. We don’t know her nearly well enough. I don’t care about them as a couple. What’s their history? Who cares? The more I think about this element of the film, the more I consider it a real failure to develop something that could have resonated quite powerfully. It’s a missed opportunity, in my book.

James: Earlier, I mentioned the structure of the film. This steamy affair happens right in the middle. A part of me likes the fact that this comes when it does. I’d be interested to watch Topaz again and focus on the structure to see if the film is like walking up and over a pyramid … each side a mirror image of itself, in which the beginning and end match in style and theme.

Jason: That’s an interesting theory about the pyramid structure, but I’m not sure what it means in the context of the rest of the film. But there’s a definite statement in this film about sexual infidelity versus political infidelity, so you can make a case about the symbolic weight of Andre’s steamy affair balancing the film’s preoccupation with political betrayal, but I can’t get beyond the fact that his affair with Juanita makes him a bastard. You usually have problems with such obvious two-timers, don’t you?

James: I have no problem with the affair. Why should I? Almost all of Hitch’s men have affairs. I also like the fact that Juanita is running this underground rebellion. But that isn’t the focus of her character, which is good. We just get to see a scene or two of that and how it affects her.

Jason: I think the less we talk about her little rebellion, the better. It really amounts to a couple of yahoos who walk up to a hill overlooking what I assume to be the Bay of Pigs and taking some pictures of ships and missiles. Significantly, we get some bird symbolism at this point, with gulls stealing these would-be picnickers’ bread and alerting Cuban police, and the man and woman are chased down in a silly little pursuit sequence, then taken to prison and brutally tortured. Nice job, guys. Thanks. Now Juanita is doomed. I got another laugh during the stock-footage rally with Castro. Parra’s henchman spots Andre in the crowd, recognizing him from the chase in New York, then whispers to Parra about him. And he says, in all seriousness, “You want me to beat him up?” Hahahaha!

James: There are some silly moments. I laughed at a few points, too. But, man, you just didn’t like this one.

Jason: At any rate, Andre is fingered, and Parra tells him to get the hell out of Cuba. And here comes one more great scene: Juanita’s death at the hands of Parra. He confronts her with the knowledge that she’s been leading this resistance and taking spy photos, and he embraces her, murmuring slowly, almost passionately, about how she’s going to be tortured and imprisoned—and then he shoots her. Love the way her lavender gown spreads across the checkered floor like blood.

Jason: At any rate, Andre is fingered, and Parra tells him to get the hell out of Cuba. And here comes one more great scene: Juanita’s death at the hands of Parra. He confronts her with the knowledge that she’s been leading this resistance and taking spy photos, and he embraces her, murmuring slowly, almost passionately, about how she’s going to be tortured and imprisoned—and then he shoots her. Love the way her lavender gown spreads across the checkered floor like blood.

James: The way her gown spills open is so perfectly done. It’s like a pool of blood. This is one of the best shots of the film. Very nice indeed.

Jason: Worthy of a better film.

James: So, when Andre gets home, we find that Nicole has left him. I assume this means that she needs no real proof of their affair to leave her husband? I mean, did she totally just not believe him when he left? Seems a little odd.

Jason: That’s an interesting point. I think this is a case of Hitch manipulating his audience, essentially giving the wife the same information the audience has. In other words, since we’ve seen the infidelity, she must have, too. I didn’t even notice. Good catch.

James: But whatever. At the party we find that Jacques Granville (Michel Piccoli)—an old friend of the Devereauxs—has been in love with Nicole for a long time. I thought this was a weak twist this late in the film. It really holds no power here, in part because the wife has so little to do with the story. Sure, it sets up a little what comes later, but it’s not worthy of many other Hitchcock love triangles.

Jason: Yeah, at this point, the story is really getting out of hand for me, particularly for the reason you mention. We meet Jacques, who’s apparently the man code-named Columbine, the head of the Topaz organization—which, we find out now, is a group of French politicians who work for the Soviets. Jacques is the secret lover of Andre’s wife, and even though this affair contributes to the movie’s theme of political and marital infidelity, it feels false. I mean, earlier, she was all tearful and hysterical about Andre’s affair. This feels sloppy.

James: I hadn’t thought of that. Why would she be all sad if she too were sleeping around? Maybe she’s not interested in Jacques until she goes to him for support? Who knows. What gets me is Andre’s daughter, Michele. She seems so indifferent about everything. “Oh, mom’s gone. Pass the salt.” That’s what it felt like to me.

Jason: Speaking of Michele, she was a hot little number. But I never got the feeling that she was really their daughter. I never felt that they were a family.

James: She was hot indeed. I was hoping she’d be Topaz or something. Anyway, although the movie does fall apart a bit, we still have some decent scenes left. The luncheon scene—in which Andre arranges a get-together with some political figures to try to root out the key members of the Topaz organization—is pretty good. Nothing great, but it does push the rest of the story along and makes a good segue to Francois’ interview scene with Henri Jarre (Philippe Noiret).

Jason: I do like that Andre has his suspicions about Henri, and keeps giving him these sidelong glances at the table. And I liked the revelation from Henri that Kusenov is dead, leading us to wonder who the man with the CIA is—is he an impostor? No, the reality is that Henri is lying—quite well, in fact.

James: All of these later sequences work for the most part, but they sure came fast and furious. It almost feels as if Hitchcock was trying to cram an hour’s worth of scenes into 20 minutes. Good grief. C’mon, Hitch, slow it down. I mean, from the time Andre returns from Cuba to the end of the film, that really could’ve been the bulk of an entire film. Hell, the more I think about it, what’s the point of having the Boris character in the beginning? You could easily cut out the entire first 30 minutes of this movie and have no problem. I imagine the original Leon Uris book is 900 pages long.

Jason: You’re right, the last half hour feels compressed. A lot of plot just flashing by. And yet the whole interview sequence that Francois has with Henri is very talky. However, we do get yet another “betrayal,” or lie, in this film, this time as Francois deceives Henri to get the information he needs. I do like the way Francois boldly confronts Henri with the lie about Kusenov’s death. “You were Kusenov’s contact!”

James: I thought the interview was talky too, but in a good way. Knowing what we know and knowing that Henri doesn’t—well, that makes the scene pretty tense. By the way, I’m not sure why, but I really like the Francois character, and I like how his sketch ends up later shedding light on the whole mystery because Nicole recognizes Jacques.

Jason: That is a nice scene when Nicole recognizes Jacques as the head of Topaz in Francois’ sketch. But did you catch that incredibly corny shot of Andre glancing wistfully at a framed photograph of the three of them—he, Nicole, and Jacques—enjoying some vacation time together?

James: Hilarious. Hahaha. Too bad. Did you think Francois was the dead man on top of the car? I did. I thought that was a great setup. But to be honest, I was actually hoping it would be Francois instead of Henri. Imagine how that would’ve played out. Of course, it would’ve probably made the film another 30 minutes longer, but the family dynamics would’ve been fun to watch.

Jason: No, I figured that would be Henri on the car. When Francois gets Henri to agree to talk about his involvement with Topaz, I figured Henri was just stalling so that he could commit suicide. I didn’t figure he’d be killed by the Topaz thugs to make it look like a suicide.

James: A lot of this stuff is unclear.

Jason: Yes, this specific section of the film feels glossed over to me, in a confusing way. Seems that too much time is spent, for example, just watching Andre look in the phone book and laboriously dial Henri’s number, and get no answer. He even says, “There is no answer.” Why are we seeing this stuff? It’s stopping the film dead in its tracks when we should be on the edge of our seats, wondering what’s happening to Francois … What happened to Hitch’s technique?

James: It seems that a lot of Hitchcock’s “thinking” has disappeared to be replaced by vocal explanations. “There is no answer.” Duh! I found that irritating, too.

Jason: What did you think of the shots of Andre and his daughter running up and down those stairs to Henri’s apartment? What the hell was with that music?

James: Well, first of all, we have the age-old stair symbolism at work, suggesting that they’re not going to find anything pretty. But yeah, there are indeed some bad musical moments in this film. Perhaps more important, why is Michele going to Henri’s, anyway? Andre is rushing into danger with his daughter? I don’t think so.

Jason: Well, I can see her rushing out with him, because she’s concerned about her husband, Francois. But it’s all so rushed and fragmented that we don’t really make the emotional connection. I did like Francois’ line, when we meet up with him again: “I’ve been shot, just a little.”

James: What did you think of that anticlimatic ending? All this running around to find Topaz and to find the leaks, and the only thing that happens to Jacques is that he’s asked to leave that meeting room? Even the alternate endings presented on the DVD are bad. Would it have been so hard to make Jacques run? Or have him get shot or something?

Jason: I actually didn’t mind the quiet ending … that something so huge and ominous ends with a whimper. Jacques is very quietly told to leave the room of ambassadors, and it’s shot from this nice God-like angle, and that means that Topaz is finished. Just like that. That’s okay in my book. What fascinates me about the three endings that Hitch shot is that his preferred ending is so monumentally bad! I mean, was he so out of touch politically to think that a pistol duel is the best way to resolve this story? I also thought it was interesting that the DVD’s feature presentation gives us the ending that’s the second-worst—of Jacques leaving on a plane to the Soviet Union, just as Andre and Nicole (suddenly reconciled) leave on a plane for the United States. In this ending, Jacques is free and smiling, and Andre and Nicole have very quickly forgiven each other’s betrayals, and all is good—and unresolved for everyone. The best ending is the one that the general public saw during the theatrical release, of Jacques going quietly home and shooting himself, off-camera. Then, cut to the newspaper that says Cuban Missile Crisis Over. Nothing wrong with that ending at all. Why does the DVD end with the wrong ending?!

James: I forgot about that suicide ending. I liked that one the most, too. And I didn’t so much mind the fact that Jacques is forced to leave the room, but having him happily board that plane and smile across the way at Andre as if they’re still best friends … that was just plain silly. Oh, and I didn’t know the suicide was the ending the public saw. Interesting. I wonder why they switched ’em up.

Jason: Still wondering about that one. It’s mystifying. I gather that this film had disastrous sneak previews. The audiences hated the ending with the duel, so the studio insisted that Hitch shoot a different ending. He had to scramble to assemble the suicide ending from footage already shot. So it isn’t the most polished sequence, but it’s the best one dramatically.

James: Agreed.

Jason: So, Hitch’s process shots are all over this film. What are your thoughts on them, at this point in his career? Artificiality or stylization? Do they make these films uniquely Hitchcockian, or are they the hallmarks of a lazy man who just liked to sit in his chair on the set? They seem to be more and more obvious, perhaps because the films around him are increasing in their realism? At this point, Hitch’s techniques are becoming downright archaic. Thoughts?

James: His process shots have never really been a problem for me until these later films. It seems that technology and filming improvements have made giant strides and totally left Hitchcock in the dust. It’s like a modern movie being made with models instead of CG. I can’t quite put my finger on what it is, but these movies don’t feel like Hitchcock. My first reaction is that they are too open. The earlier pieces are shot in a studio and feel claustrophobic, while these later films are wider, more open. This makes his process shots stick out in a bad way. The great Hitchcock films always felt like classic old movies. These recent ones feel like bad modern movies.

Jason: Man, you hit the nail on the head with that one. I hate to say it, but there’s a kind of pathetic quality to some of these techniques. One last thing I wanted to mention. The biography mentions this huge project that Hitch was working on just prior to embarking on Topaz. Called Frenzy (but a different project from the film a few years later), this was a Jack the Ripper type film that would use the cinema verite style and feature lots of sex and nudity, natural lighting, and a Howard Fast screenplay. This project had a long prep time, and many think that it’s the greatest film that Hitch never made. The reason it stalled was Universal, who objected to the focus on nudity. It was too risky. So, Hitch grabbed at Topaz and made it quickly. It’s really a sad story. Would have been a great swan song.

James: That sounds like a great little film. Can you imagine Hitchcock doing a Jack the Ripper story? Actually, I think Frenzy might turn out to be a bit Jack-the-Ripperish. Isn’t there a knife and lots of killing in this next one?

Jason: That’s what I’ve heard. I’ve never seen these last two films.

James: I still think, overall, that I enjoyed Topaz. There’s a lot wrong with it, but the story is just good enough for me to probably be willing to watch it again someday. That being said, are you feeling bad for Hitchcock at this point? I almost feel sad that he didn’t go out on top. It’s sort of like watching Brett Favre, or any other sports hero. They get old. They get washed up. They lose their luster. And it feels weird to know that this great man is fallible. I won’t say that I’m making excuses for him, but at times, I feel like I need to find something valuable in these last three movies. Like, if I don’t like them, my memory of him will be tainted. Does that make sense? After a yearlong look at his films, I’m feeling almost emotional that these last three won’t be on par with what’s come before.

Jason: Yes, I’m feeling these things about Topaz in particular. (I think it’s quite appropriate that Hitch’s cameo in this film has him seated in a wheelchair.) But let’s not count out the old guy yet. I think we may be in for a few surprises as we finish up the final two films. I’m not going to say he’ll go out on top, but I think there will still be some things to admire in the next two weeks. And I wouldn’t say that a misstep like Topaz takes anything away from his legend. He’s made bad films before. Look at Jamaica Inn and Under Capricorn. He was apathetic with those, too. I’m not ready to sound Hitch’s death knell.