The Hitchcock Conversations is an ongoing project between me and James W. Powell, in which we study Alfred Hitchcock’s filmography in chronological order. I’ll be publishing one conversation per week.

The Hitchcock Conversations is an ongoing project between me and James W. Powell, in which we study Alfred Hitchcock’s filmography in chronological order. I’ll be publishing one conversation per week.

(By necessity, spoilers ahead!)

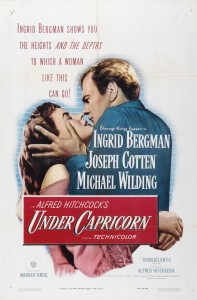

Synopsis: In 1831, Irishman Charles Adare travels to Australia to start a new life with the help of his cousin who has just been appointed governor. When he arrives, he meets powerful landowner and ex-convict Sam Flusky, who wants to do a business deal with him. Whilst attending a dinner party at Flusky’s house, Charles meets Flusky’s wife Henrietta, who he had known as a child back in Ireland. Henrietta is an alcoholic and seems to be on the verge of madness.

Jason: Urgh. I don’t think this movie will inspire a lot of conversation. I think Under Capricorn is a tedious, dialog-drowned movie that’s just endless talking and no “showing.” It feels to me as if Hitch was never comfortable filming it, and a little history reveals that that was the case. It was a troubled production from the start, and in fact Hitchcock was intoxicated by the idea of returning to England with the biggest star of the day, Ingrid Bergman, and filming a big historical epic on his native soil. Unfortunately, Bergman was a prima donna by then, and tension on the set spread throughout the entire shoot. You can almost feel that tension on the screen, almost a sense of actors wanting to be done with it.

James: Talk talk talk talk talk. Good grief. This is the most un-Hitchcock film we’ve seen in months. There are some interesting elements, but man, this film fell flat for me. Not sure if it was because of the location or the story, but I’d just as soon we never see another period piece.

James: Talk talk talk talk talk. Good grief. This is the most un-Hitchcock film we’ve seen in months. There are some interesting elements, but man, this film fell flat for me. Not sure if it was because of the location or the story, but I’d just as soon we never see another period piece.

Jason: Well, this is the last one.

James: Good!

Jason: The plot just isn’t very interesting, or it feels as if we’ve seen it all before. From what I gathered, our protagonist is Charles Adare (Michael Wilding), the nephew of an Australian governor (played by Cecil Parker, who played Mr. Todhunter in The Lady Vanishes). Adare has come to Australia for land and fresh prospects. He quickly meets Sam Flusky (Joseph Cotten), a gruff sort who offers Adare a shady land deal. We come to find out that Sam is an ex-convict exiled to Australia for murder. We also find that he’s married to Lady Henrietta (Ingrid Bergman), a sick, tragic figure seemingly imprisoned in the Flusky mansion. There’s some kind of dark cloud over the house, and Adare makes it his mission to cure Henrietta (Hattie), who is also his cousin, of her strange illness and figure out the mystery of the household.

James: I’m yawning just thinking about it.

Jason: I agree. It’s like anything interesting in the film, any sense of mystery, is drowned out by an ocean of dialog. Characters talk and talk about their histories and predicaments, and we don’t really care because we’re not seeing any of it, we’re just hearing it all secondhand.

James: Yep.

Jason: One thing I did pick up while watching, and learned more about while reading, is that Under Capricorn, even though it’s a 19th century costume drama, has a lot in common with a few of Hitch’s most recent films of the period. It’s got a long-held guilty secret (as in Rebecca). It has the specter of abnormal psychology (as in just about every Hitch flick). It’s got a wealthy woman who has married a groom, beneath her class (shades of The Paradine Case). It’s got a displaced heroine, as well as a gloomy, moody estate (as in Rebecca and Jamaica Inn). It has a gradual poisoning (as in Notorious), and it’s got an evil, domineering housekeeper (as in Rebecca). And, of course, it’s got the long, uninterrupted takes that Hitch presumably got hooked on in Rope. Finally, it has the specter of infidelity, which we’ve seen in many Hitch films. I guess that’s the most interesting way for me to approach this film, seeing it as an unnecessary patchwork creation assembled rather clunkily from pieces of his past work—except set against 1830s Australia.

James: I noticed most, but not all, of the elements you mentioned that have roots in previous Hitchcock films. But it’s almost as if there are too many here. Which ones are we supposed to focus on? There’s not really much of a love triangle, and we never really get a firm grasp on Milly, the housekeeper. Had either of these subplots been nixed, the other could’ve been amplified for the better.

Jason: I do like the whole notion that Hattie is under the spell, literally and figuratively, of her evil housekeeper Milly, who has been poisoning her with alcohol and dark magic for years. Milly’s in love with Sam and wants Hattie out of the picture. The business with the shrunken head is pretty gruesome, like something out of a horror flick. I like the idea of Milly becoming an Iago figure, enflaming Sam into a jealous rage over Hattie and Adare’s developing friendship.

Jason: I do like the whole notion that Hattie is under the spell, literally and figuratively, of her evil housekeeper Milly, who has been poisoning her with alcohol and dark magic for years. Milly’s in love with Sam and wants Hattie out of the picture. The business with the shrunken head is pretty gruesome, like something out of a horror flick. I like the idea of Milly becoming an Iago figure, enflaming Sam into a jealous rage over Hattie and Adare’s developing friendship.

James: I too liked the idea of Milly, but her story wasn’t brought forward soon enough. Had she been a key player, it could’ve worked.

Jason: It felt like Milly was supposed to be an essential character. And you know, as much as I like the idea of Millie’s Iago scene, in which she suggests that Adare is sleeping with his wife and drives Sam to murderous thoughts, the execution was laughable. It’s supposed to be horrifying, but the writing is just so stilted and overdone, and even the onscreen blocking is awkward. I never thought I would say this, but Hitch has directed a really terrible scene of suspense.

James: Yep, Milly really should’ve been central. If the scene with her and the shrunken head and the poison would have had some careful build-up, both the scene and the character might’ve had some suspense around them.

Jason: The big confession scene, in which Hattie confesses to the crime of killing her brother—the crime for which Sam took the blame and ended up in exile—felt completely anticlimactic to me. I recognize that Bergman’s performance is good, and I like that this is one of the film’s long takes. Bergman goes for broke in the scene, going from calm and quiet to passionate and almost hysterical, very gradually. But I couldn’t get myself to feel for the character. In another movie, perhaps, it would have gotten to me, but in this movie, it’s just . . . yawn.

James: I actually thought the story got interesting at the end. Hattie finally gets out of the house, and suddenly her husband goes on a jealous rampage. Even better, Sam has to decide whether to let himself die or see his wife in prison. Now there’s a story. Cut the first 75 minutes down to 15, and expand the suspense around whether he’ll let his wife take the fall, add the housekeeper and maybe a suitor for the wife, and you might have something.

Jason: You’ve boiled the plot down to something that might have been involving. The really interesting plot is Hattie coming out of the house, breaking free of the bonds that keep her there, and the reaction on the part of her husband. The key to making it work would be to actually have some scenes illustrating the conflict that Sam feels, rather than just spouting out of the mouths of characters in parlors and on verandas.

James: You know, in the film, Sam never really seems like that bad of a guy. He’s made out to be this great evil, but I never really felt that. Maybe Hitch was trying to add an element of mystery to his crime, but it didn’t work for me.

James: You know, in the film, Sam never really seems like that bad of a guy. He’s made out to be this great evil, but I never really felt that. Maybe Hitch was trying to add an element of mystery to his crime, but it didn’t work for me.

Jason: One of the film’s more interesting aspects is that Sam at first seems to be a gruff asshole, but it turns out that he’s been suffering inside because of what he’s sacrificed for his wife. Should that aspect have been explored more, or is it best left to a character revelation, as it is? Did you think Cotten was miscast as Sam?

James: Cotten wasn’t necessarily miscast, he just wasn’t given the proper screen time. I really like the way Sam handles the dinner party early in the film. Something is amiss, but he isn’t necessarily a bad guy. You know there’s something wrong between Sam and his wife. As I said earlier, I think his suffering could’ve been the revelation, but Hitch should’ve followed through with it. That’s really powerful stuff. The last 20 minutes of this film could’ve been the whole movie. A good movie! Sure, it was a cool revelation, but it could’ve been more powerful had Sam been on camera when the cat was let out of the bag. I always hate thinking about what could’ve been, but man, there’s some good stories in this film that aren’t showcased the way they should’ve been.

Jason: Indeed, it’s a mess. I think it’s interesting that Hitch’s first film back in the UK was a costume drama—just like his last film in the UK before leaving for the states, Jamaica Inn (which, incidentally, has a very similar early shot of a stranger arriving at a mansion in a carriage). You’d think Hitch would have learned from his first failure with the costume drama.

James: It is odd that Under Capricorn and Jamaica Inn are two of the worst films in his career. (As for your parenthetical comment, we know that Hitch rips himself off incessantly.)

Jason: Speaking of repeated motifs, I did notice the symbolism of the stairs at work in this film: An elaborate stairwell leads to Hattie’s room, where she’s being slowly poisoned to death by Milly.

James: Yeah, the stairs are rather obvious in this film, and they’re used frequently. I’m surprised someone didn’t stumble down them.

Jason: What did you think of the long takes, anyway? I found them intrusive. They almost made the film seem even longer. The camera seemed even more mobile than in Rope, climbing floors in the house and winding through rooms. But there are also a lot of stationary shots, where we just watch people sit and talk. I guess one of the things Bergman complained most about was the long takes, getting downright enraged at points. I’m sure that helped the atmosphere of the set.

James: The long takes definitely add to the film’s length. There are far too many of them. One, however, stood out to me: The scene in which Milly gathers the empty alcohol bottles from Hattie’s room and humiliates her in the kitchen was well done. But in most cases, everything dragged on and on.

Jason: So, do you think Hitch made a mistake hiring Hume Cronyn as the screenwriter? He was a good friend of Hitch’s and had good ideas but was inexperienced at writing for the screen. How much of Under Capricorn can we blame on the writer and how much on Hitch?

James: Well, you have to blame the screenplay on all that dialog, so there’s no getting around that. But Hitch didn’t help by deciding to cut the film the way he did. There are really no creative camera angles in this film, either. Nothing really Hitch at all.

Jason: You do get the sense he was phoning this one in.

James: Oh, and why did we need to see the governor taking a bath? I mean, what was up with that whole bathtub scene, anyway?

Jason: Yeah, I didn’t need to see the governor of Australia naked in a tub. And, curiously, it’s one of the film’s really long shots, making me think that Hitch attached some importance to it. Or maybe he just wanted to shoot it that way for the challenge of it, going up a floor and flowing through doorways as it did. But the scene did make me think of that episode of The Simpsons where the family goes to Australia, and there’s a scene with the governor in a bathtub. So what’s with all the naked Australian governors?

James: This film starts off on the wrong foot, too. Why take 10 minutes to establish the governor and his cousin, Adare? The film should’ve gone right to the bank for the introduction of Sam.

Jason: I guess Hitch was just establishing the setting. But, yeah, it was boring and unnecessary.

James: Honestly, I never thought the whole period setting worked, either. I know nothing of the place or time period, so maybe that’s why none of that worked for me.

Jason: That being said, one thing I like about the film is its color palette, which feels lush and subtropical in the right spots. Many scenes have a fiery, red-orange quality that make the Australia setting seem real.

James: The only thing I really noticed about the color is that Adare, originally from Ireland, wore bright green the whole time. Luck of the Irish, anyone?

Jason: Speaking of the film’s look, there are some impressive matte paintings at the beginning.

James: Yeah, I noticed the matte paintings. Very well done, indeed.

Jason: Any thoughts about Hitch’s production company Transatlantic, which tanked after this film? Was it a doomed endeavor from the start?

James: I can’t believe it tanked after just two films. Maybe it would have caught on if he hadn’t created this stinker. Did Under Capricorn flop at the box office?

Jason: Yeah, it completely tanked at the box office. Apparently, it cost a whopping $2.5 million to make, a lot of which went toward Hitch’s and Bergman’s salaries. The film flopped rather quickly and was reclaimed by the bank that financed it. In fact, prints of the film were unavailable for a long time because rights to it were held back for years. Perhaps it should have remained that way.